Reports of Psychiatry Abuse

Counter Talk of a Soviet Shift

Reports of Psychiatry Abuse

Counter Talk of a Soviet Shift

Reports of Psychiatry AbuseCounter Talk of a Soviet Shift By Felicity Barringer, special to the New York Times

Published: October 21, 1987

LEAD: A political dissident recently released from a Soviet psychiatric hospital said today that the habitual use of punitive psychiatric treatment in the Soviet Union remained unchanged despite recent criticisms of such practices in the Soviet press.

“There are no changes,” said the dissident, Vladimir Titov. “On the contrary, it’s getting nastier.” Mr. Titov was released Oct. 9 from the special psychiatric hospital in the Russian city of Oryel.

Mr. Titov said his most vivid recollections were of two strong psychotropic drugs that caused fever, pain, slurred speech and left him unable to lie, sit or stand comfortably. He also spoke movingly of dissidents still inside, while other human rights advocates at the news conference played a tape of another patient, Sirvard Avakian, an Armenian dissident, asking in a trembling voice for Western help in releasing her from what she described as the abuse of her doctors.

This account of the dark side of the Soviet psychiatric system – which differs hardly at all from the horror stories told a decade ago by a dissident psychiatrist, Anatoly Koryagin, and other human rights advocates – comes just as Soviet medical authorities seem eager to rehabilitate their image.

Two events of the last year seemed, to some observers, to offer Soviet doctors a chance to end their five-year ostracism from the world psychiatric profession.

A Series of Articles

The first was Mikhail S. Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost, or openness, which this year produced a series of articles in the Soviet press detailing unsanitary and crowded conditions in psychiatric hospitals, and revealing the practice of doctors’ accepting bribes from criminals in return for a diagnosis of mental

illness – saving the criminals from serving sentences in labor camps.

Most surprising was an Izvestia article that described with outrage instances of local police and bureaucrats who tried to force the psychiatric commitment of two women who had simply argued too long with authorities. One was committed and one evaded it by barring herself in her bedroom while the family fended off doctors and their aides.

“Although the subject of the article isn’t dissidents,” the Soviet historian Roy A. Medvedev said in a recent interview, “the mechanics of psychiatric abuse become perfectly clear because in these articles the diagnoses are disputed.”

“And if this sort of thing can be done to an average woman who complains about simple matters, it’s all the easier to do it to a dissident,” he added.

Another article, in the weekly ideological journal Arguments and Facts, said that in 1985, 1,923 of every 100,000 Soviet citizens were registered as having psychiatric disorders, indicating that more than 5 million in the country have such disorders.

The other supposed opening for changes in Soviet psychiatry came with the death last summer of Andrei V. Snezhnevsky, the Soviet psychiatrist widely seen as being responsible for designing and defending a system of diagnosis that equated nonconformity with illness.

To some experts, Dr. Snezhnevsky’s death offered Soviet doctors a chance to repudiate his legacy and construct a new theoretical underpinning for Soviet psychiatry. There has even been a recent suggestion, during Foreign Minister Eduard A. Shevardnadze’s recent visit to the United States, that Soviet psychiatrists might strike from their textbooks a key Snezhnevsky diagnosis.

This diagnosis, called “sluggish schizophrenia,” is said to manifest itself in obsessive desires “to seek social justice” and said to be camouflaged by seemingly normal behavior. It was this diagnosis that was made in the case of Mr. Medvedev’s twin brother, Zhores, during his brief forced commitment in the early 1970′s, and also in the cases of the women profiled in the Izvestia article.

Leading doctors who have long defended Soviet psychiatry took umbrage at the Izvestia article, responding in an interview with the Novosti press agency that both the women in question were indeed ill.

“In the instances described, the two women were in conflict with many people,” said Marat Vartanyan, a corresponding member of the Soviet Academy of Medical Sciences. “They suffered themselves and caused suffering to others. They not only made unsupported complaints but accused others of conspiracies.” “Psychiatrists have a duty to safeguard society from disorganizing and sometimes dangerous steps by the insane,” Dr. Vartanyan added.

Transfer Is Considered

Dissidents assert that the K.G.B. runs the system – an accusation supported by the fact that the Ministry of Internal Affairs controls the 18 special psychiatric hospitals. However, there have been reports in the Soviet press that authorities are considering transferring this responsibility to the Ministry of Health, already responsible for the management of “ordinary” psychiatric hospitals and clinics.

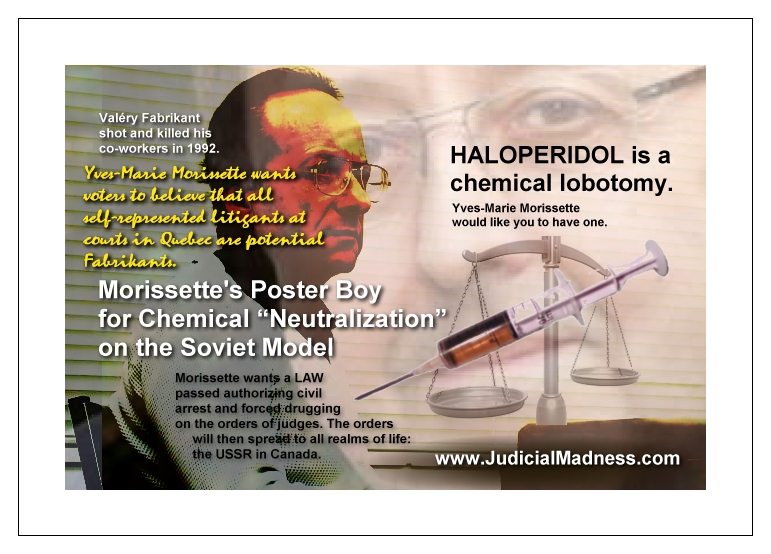

And the doctors interviewed by Novosti said a new law was being formulated to delineate mentally ill persons’ rights to housing and employment, and to clarify procedures for involuntary examinations and hospitalization.

But Mr. Titov and members of the Frankfurt-based International Committee on Human Rights, whose Moscow branch sponsored today’s press conference, argue that management or theoretical changes will have no effect on curbing psychiatric abuse, any more than the recent release of several dozen dissidents in psychiatric hospitals.

“The structure doesn’t have to be changed,” said Aleksandr Podribinek, who has written a book on Soviet psychiatric practices.

“Psychiatric abuse is the result of bad politics, not bad psychiatry. To stop abuse we have to change the politics.”

K.G.B. Came to Hospital

If the diagnosis of “sluggish schizophrenia” were eliminated, he said, “this might be taken as a sign of some change – but a very unreliable one – and they’re committing healthy people using other diagnoses as well.”

Mr. Titov said that when he was released from the hospital Oct. 9, “it was the K.G.B. who came to the psychiatric hospital to talk to me and to try and persuade me to give up my convictions.”

Mr. Titov, whose 1982 reports of convict labor on the Siberian gas pipeline were cited as partial justification of the American-led embargo on pipeline equipment, said he was freed on condition that he immediately emigrate to Israel. Mr. Titov, who is not Jewish, has no relatives in Israel.

In general, Mr. Titov and other members of the committee said Monday, dissidents evoke particular ire on the part of authorities and are often given harsher punitive “treatment,” in the form of injections, than the other inmates of the country’s 18 special psychiatric hospitals.

Mr. Titov spent the last five years in psychiatric hospitals as a result of the pipeline revelations, and in total has spent 12 of the last 18 years in such confinement.

Sergei Grigoryants, the editor of the magazine Glasnost, said yesterday he could not estimate the scope of psychiatric abuse in the Soviet Union, but added that anecdotal information about recent commitments led him to believe the system is still widely abused. “We’re not doctors,” added Vladimir Pimonov, a member of the human rights group. “We can’t say that all these people who are committed are healthy. But to shut them in a special psychiatric hospital is inhuman. They’re not murderers or terrorists. Their only crime is speaking their minds.”

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company