In Two Minds about Soviet Psychiatry

14 October 1989

NewScientist.com news service

DAVID COHEN

NEXT WEEK, the World Psychiatric Association will decide whether to let the Soviet Union back in. The Soviet Union resigned in 1983 rather than answer a debate on the political abuse of psychiatry. Already, the battle lines have been drawn between those committed to allowing the Soviets back and those who believe it would be premature. Sceptics want better safeguards before the Soviet Union is made respectable again.

The Soviet resignation followed 12 years of lobbying by political dissidents, such as Vladimir Bukovsky who was held in the Leningrad Special Hospital, and academics such as Sidney Bloch, then of the University of Oxford and now at Melbourne University, and Peter Reddaway of the University of London. Their books, Russia’s Political Hospitals (1977) and Psychiatric Terror (1984), alleged that many dissidents had been diagnosed as insane to punish and gag them. The dissidents were held in appalling conditions in special hospitals designed for the criminally insane. Often, they were beaten and forced to take unnecessary drugs. The aim was to use psychiatry to break them.

Many Western governments and independent groups such as Amnesty International supported the allegations, and the Russians closed ranks. Psychiatry became a taboo subject in the country, and Western doctors and journalists were rarely allowed to visit even ordinary Soviet psychiatric hospitals. Perestroika and glasnost have now made that policy counterproductive. Soviet politicians are embarrassed by the accusations; they want an end to the controversy and the Soviet Association of Psychiatrists back in the World Psychiatric Association. But they seem to want to give as little as possible for it.

There have been psychiatric abuses in many countries, but the Soviet Union was the only country to use it for such obvious political ends. The West saw that as a reflection of the iniquity of communism, and critics focused on political dissidents as if they were the only issue in Soviet psychiatry. In fact, the unjust treatment of dissidents could not have happened if the whole of Soviet psychiatry was not exceptionally authoritarian. One of the facts not appreciated in the West is that the Soviet Union has a register of 5.5 million patients who are considered ‘socially dangerous’ – that is, nearly 2 per cent of the whole population. These patients are very rarely ‘politicals’ but can be taken into hospital at any time and are, in effect, on perpetual probation. In Britain about 17,000 people a year are compulsorily detained.

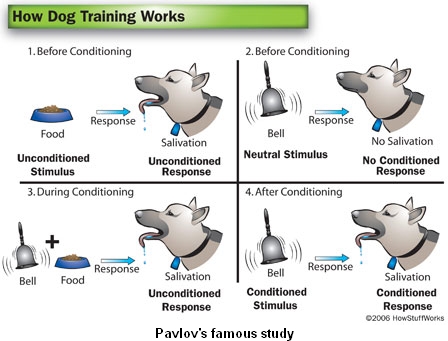

Soviet psychiatry is a paradoxical art and science. It is meant to be Marxist. According to Karl Marx, human beings are social animals. If people are sick, it must be the result of their social interactions. The way society treats them is critical. Despite this ideological background, Soviet psychiatry is the most biological in the world. It almost totally ignores social factors in practice. It is still dominated by the legacy of Ivan Pavlov.

Pavlov won the Nobel prize for physiology in 1904 for his work showing how he could condition dogs to salivate to a bell rather than to food. Experimental studies of human learning have made much use of Pavlov’s ideas. Lenin protected Pavlov and provided his laboratory with special food for the dogs when the masses were starving.

Pavlov’s prestige was so great that he controlled Soviet psychology and psychiatry. He thought mental illness was essentially organic. As late as 1950, 14 years after his death, a joint meeting of the Academy of Science, and the Academy of Medicine castigated those psychiatrists who dared to criticise Pavlov’s theories. Today, at the All Union Psychiatric Institute in Moscow, most of the research remains biological. A central focus is on childhood schizophrenia. One senior researcher on the children’s ward claims that she can detect schizophrenia in some children at birth. The possibility of a genetic basis for schizophrenia is controversial; but in the West no one would claim to be able to detect schizophrenia in babies.

There is no logical reason why a biologically inclined school of psychiatry should treat patients more harshly. Yet it often seems to happen. In the Soviet Union, both ordinary and political patients tend to be seen not as people but as sick objects. They are not fit to have rights, let alone a say in their treatment. Their biology just is not up to it. This created a dismissive attitude that made it easier to detain dissidents. By definition, in a dictatorship, people who question political orthodoxies tend to appear quirky and difficult.

To help to convince the world that their psychiatry is changing, the Soviets have now started to encourage some contacts. Earlier this year, I was given a surprising degree of access to both ordinary Soviet hospitals and to some of their most ‘notorious’ institutions including the Serbsky Institute of General and Forensic Psychiatry and the Leningrad Special Hospital.

The Serbsky is a focal point of Soviet psychiatry. It is a drab complex of buildings in central Moscow, guarded by the militia whom I was asked not to photograph. It was a strange request, given that the Russians argue that most of those sent there for assessment have committed violent crimes.

The Serbsky assesses people who have been accused of crimes anywhere in the USSR. It sees all the tricky cases, and all the political dissidents were tricky. If the Serbsky judges a prisoner to be mentally ill, he or she is usually sent to one of the Soviet Union’s 16 special hospitals. Dissidents often said that treatment at the Serbsky was not bad. ‘It was a hotel but a hotel on the route to hell,’ according to Alexandsr Podrabinik, the Moscow representative of the International Association Against the Political Use of Psychiatry.

I was allowed to visit only one ward and to see the psychology department. The ward was badly overcrowded, with 43 people sleeping in three rooms. But I was allowed to talk fairly freely to patients, who were all dressed in blue uniforms. Glasnost had arrived, for patients felt free to criticise. One of them, Mikhail, asked to speak to me. He had just spent 3.5 years in Oryol Special Hospital. He said he had read that these hospitals had been transferred from the Ministry of the Interior to the Ministry of Health. But this liberal move had ‘made practically no difference’. Not only were the watchtowers and machine guns still in place, ‘but the hospital was dirty and discipline severe’. Staff often stole things both from the hospital and from the patients, he said.

The Serbsky psychiatrists were embarrassed, but they did not try to stop the patients criticising or to discredit their views as ‘mad’. In the psychology department, the tensions under which the hospital now works became clear. I was allowed to sit in while patients did rather crude psychological tests – mainly sorting picture cards into categories. This, I was told, offered scientific proof of organic damage.

In visits to two non-secure facilities in Moscow and Leningrad, the staff told me that criticism from the patients was proof of their madness. At a local health centre in central Moscow on Chekhov Street, the doctors tried to stop me interviewing a fat, bearded man called Ephraim. At first, I thought it was because he was surly. But when I insisted, Ephraim said he hated being on the register. ‘I’m treated like a black in America,’ he said.

Ephraim alleged that he had been in trouble with psychiatrists ever since he approached the US embassy to seek to emigrate to Israel, in 1978. His doctor kept on interrupting the interview to insist that Ephraim knew that he was being controlled by voices in his head. He was mad. Ephraim sniped that if the doctor knew what he felt so well, why should he, Ephraim, bother telling anyone? After the interview ended, I was rushed into the doctor’s office to hear extracts from his clinical notes. Ephraim was a bad lot and very schizophrenic. At the Bechterev in Leningrad, when a woman called Irina complained that she had been detained unjustly, I was told she was a ‘lazy patient’. Complaining was one of her symptoms.

Scientifically, the Soviet psychiatrists justified their position by claiming that many dissidents suffered from ‘sluggish’ or latent schizophrenia. The official American Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, the Bible of psychiatry, does not accept this as a form of illness. Sluggish schizophrenia, according to the Serbsky psychiatrists such as Georgy Morosov, is a form of schizophrenia that is so subtle that only a psychiatrist can detect it. There are no obvious symptoms but the psychiatrist knows best. It seems a scientific smoke screen so that anyone who bothered the authorities could be labelled mad.

Anxiety about what patients might say was also obvious at the Leningrad Special Hospital. I was allowed to visit only one rehabilitation ward, the medical ward and an observation ward. There are 12 wards, and I could not visit the two wards for really difficult patients.

The security at Leningrad is tough. You enter through an airlock system. There are bars at every window and militia everywhere. It looks and feels like a prison. The hospital is badly overcrowded, especially its observation ward. Here 15 patients are crammed into one small room. There is no space between the beds and patients spend all day lying down under the eye of an unqualified medical orderly who watches for ‘any signs of psychosis, tears or laughter’. By themselves, the conditions are likely to provoke a breakdown.

The 790 patients at Leningrad have been sent for treatment, but in fact, they spend most of their days working. The workshops produce clothes and toys including, strangely, toy guns. Given how dangerous these patients are meant to be, it was remarkable that they used not just sharp tools but big knives in their work.

‘Too ill’ for an interview

I had been told both by the USSR Ministry of Health and by Anatoly Potapov, the Minister of Health for the Russian Federation, that I could interview any patient I wanted. Amnesty had given me a list of patients they wanted information about. One of them was Stomatislav Sudakov.

When I asked to see Sudakov, I was told I could not. He was too sick to see anyone but his doctor, according to Victor Stashkin, the director of the hospital. Stashkin denied Amnesty’s claim that Sudakov had been in special hospitals ever since he tried to enter the American embassy in 1974. Stashkin at first refused to discuss the case because it would break confidentiality to do so. Then, when I suggested this would look bad, given the new openness, he showed me the court and medical records. These claimed that Sudakov had been a troublemaker since his teens and that he had been convicted for causing criminal damage to an Italian cello at a concert in Tallinn in 1985. That was why he was in hospital. Stashkin added that it was a fine old cello, too.

But the record said that Sudakov had escaped from hospital in 1983, two years before the alleged encounter with the cello. Then, slowly, the true story emerged. Sudakov had been in special hospitals in Tashkent and Alma Ata since 1974. He had then been sent to an ordinary hospital from which he had escaped. The Western story had been fundamentally true and Stashkin’s answer less than frank.

It would be wrong to suggest that nothing has altered, however. There are signs of change from the picture painted by Bloch and Reddaway in the late 1970s and early 80s. Since then, many ‘dissenter patients’ have been released. Podrabinik said he knew of no new cases of dissidents being put into special hospitals, and only a few ‘politicals’ had been briefly detained in ordinary ones.

In 1988, a new law allowed patients to appeal against being hospitalised and against being placed on the psychiatric register. Sergei Belov, a dissident who was released from special hospital, told me that he still was not free. He had to report to the psychiatrist every six weeks. He had been offered no help in rehabilitation after years in and out of hospital. He had also been refused permission to visit East Germany. The experience had left him bitter. Many other released dissidents are on this register still, and hate it. So the new law has not yet transformed the situation. Despite the legal reform, Moscow has 200 000 patients on its register. In 1988, only four went to court to be taken off it.

Soviet politicians want to end the arguments about psychiatric abuse. But I saw little sign that the top echelons of Soviet psychiatry are willing even to admit to past mistakes. In interviews, I managed to extract only small concessions. For example, Marat Vartanyan, director of the All Union Centre for Psychiatry, said detaining Zhores Medvedev, the biologist, for 19 days had been wrong. It was not insane, he conceded, for Medvedev to press for more contact with Western scientific bodies.

‘No apologies necessary’

The new president of the Soviet Association of Psychiatrists, Nikolai Zharikov, however, was not about to issue any fulsome apologies. He told me ‘these dissidents did it for making money and their popularity’. Morosov, head of the Serbsky, flatly said that he had never known a case in which they had detained a sane person. Modest Kabanov, the director of the Bechterev Clinic in Leningrad, is seen as a liberal, but he echoed Morosov’s denial. Kabanov added that if Western psychiatrists ‘want us to do a pas de deux or a pas trois and to apologise, if they want us to bare our breast and say we were guilty’, they would be disappointed.

Vartanyan told me that he did not think the Soviet Union needed to get back into the World Psychiatric Association anyway. He was already collaborating with Western scientists, working with American and Belgian doctors in a project funded by the World Health Organization to study the biology of schizophrenia. To allow psychiatrists from other countries to check their diagnoses ‘would be professionally humiliating’, he said.

There is, however, political pressure to settle the issue. So it is not surprising that I got the most ‘concessions’ from the new director of psychiatry and narcology at the USSR Ministry of Health, Vladimir Egorov. Soviet psychiatry had tended to see ‘a very broad spectrum of people as socially dangerous’ and to hospitalise people unnecessarily, he said. People whose ideas ‘were at odds with the prevailing ideology in the country’ could have found that this was seen as a symptom of mental illness. But Egorov denied that there had been a policy of abuse and said that many of those who had strange political views might also have been ill. Egorov appealed to Western colleagues to come and see how things were changing.

Recently, a delegation from the American Psychiatric Association and the State Department visited the Soviet Union and interviewed a number of patients. Two leading Soviet Union psychiatrists, Vartanyan and Morosov, refused to meet them. There were also problems with checking medical records, partly, the delegation reported acidly, because of alleged photocopying problems.

In Britain, the Royal College of Psychiatrists has proposed that the Soviet Union should be let back into the association only if it guarantees to free all dissenter patients and ‘disassociate’ itself from past abuse.

It would be good for the Soviet Union to re-enter world psychiatry. I saw some instances of innovative treatment that the West could learn from, such as allowing patients to work productively and the treatment of alcoholics as outpatients. Many Soviet psychiatrists I met were eager for change, but many were also nervous of it. Glasnost, Vartanyan complained, had made patients aggressive. Graffiti in Moscow said ‘Kill psychiatrists’. Vartanyan quipped: ‘The only psychiatric abuse there is now is abuse of psychiatrists.’

Given the mix of novel openness but much official nervousness, some caution seems reasonable, even though, as Bloch told me, ‘one wants to welcome back 25,000 psychiatrists into international psychiatry’. At the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association in Athens, the West needs to press for guarantees that the Soviet Union will pursue the reforms and also offer some rehabilitation to patients who were unjustly detained. Only then could we be assured of an end to one of the most serious abuses of human rights in recent times.

Dr David Cohen is joint editor of Psychology News. His book Soviet Psychiatry is published by Paladin.

From issue 1686 of New Scientist magazine, 14 October 1989.