Echoes of the Past: Punitive Psychiatry by Alexander Podrabinek

Source: Echoes of the Past: Punitive Psychiatry by Alexander Podrabinek

Nation

Echoes of the Past: Punitive Psychiatry

21 October 2013

Alexander Podrabinek

In October, Russian activist Mikhail Kosenko, one of the accused in the “Bolotnaya Square Case,” was sentenced to compulsory psychiatric treatment. This was the first instance of an open use of psychiatry for political purposes in post-Soviet Russia. Author and human rights campaigner Alexander Podrabinek, who was convicted in the 1970s for his book “Punitive Medicine,” concludes that the Soviet practice of punitive psychiatry has returned to Russia.

The future is mysterious and uncertain, whereas the past is readily recognizable, familiar, and unbelievably sad. In the early 1990s, after having quickly spent its potential for reform, Russia stood motionless, as if lost in a brown study for a while, and then began slipping backward, slowly but inevitably. And the further it slipped, the faster the shapes of the past flashed before it. Elements of Soviet life began to reemerge with increasing frequency.

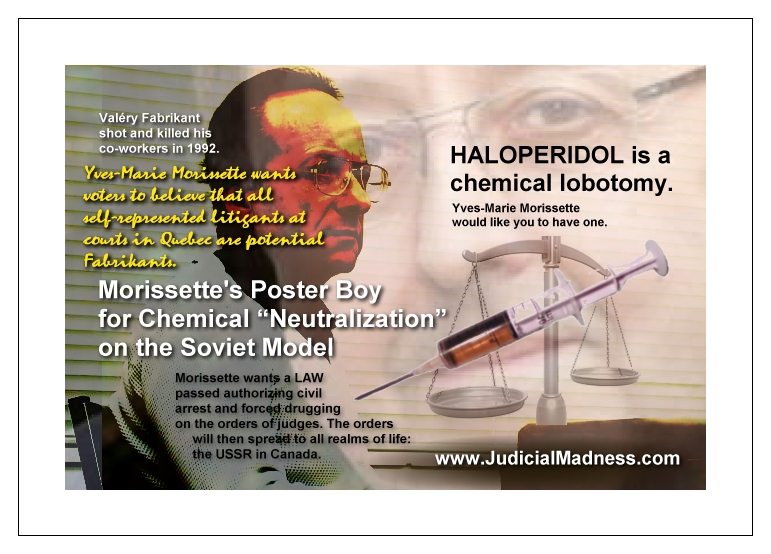

Punitive psychiatry—that is, the use of the mental health care system for the political lynching of dissidents and opposition members—has always been an inherent characteristic of Soviet totalitarianism. At times, as happened under Lenin, these cases have been isolated, such as when Left Socialist Revolutionary Party leader Maria Spiridonova and Foreign Affairs Commissar Georgy Chicherin, who stirred Lenin’s wrath, were labeled insane. During other times, punitive psychiatry was employed only in select cases, as it was under Stalin and Khrushchev. Finally, under Brezhnev and Andropov, this sporadic practice turned into a well-organized system. From the 1960s to the1980s, thousands of dissidents were put in mental health facilities, where they were subjected to compulsory psychiatric “care.”

This system started collapsing around the beginning of perestroika. The Independent Psychiatric Association (IPA), established in 1989, served as an effective public barrier to punitive psychiatry in the USSR. The fight against psychiatric abuse was and still is a major goal of the IPA. That same year, in 1989, the IPA became a member of the World Psychiatric Association.

During the first years of Russia’s democratization, laws were adopted that guaranteed patients’ rights with regard to psychiatric treatment. The practice of involuntarily committing socially dangerous patients was put under court jurisdiction. Adversarial forensic psychiatric assessment was included in criminal procedure, and special psychiatric (prison-type) institutions were put under the supervision of the ministry of health instead of the interior ministry. Other innovations appeared as well to guard against the use of psychiatry for nonmedical purposes. In essence, health care reform was being implemented in the sphere of mental treatment.

Unfortunately, the era of democratic reforms did not last. When the country stopped on its way to democracy and returned to authoritarian methods of governing, this resulted in a counter-reform in the area of Russian psychiatry and law. Adversarial forensic expertise was abolished from court proceedings, and judicial supervision over urgent hospitalization was increasingly reduced to a mere formality, as courts began losing their independence. Psychiatrists working for the regime’s interests do not fear the law or accusations of unprofessional conduct.

The system of psychiatric abuse was just waiting to be restored. And there are really no mechanisms in place to protect society from this type of abuse. Punitive psychiatry has three preconditions: falsified criminal charges, unconscientious forensic mental health assessment, and a biased justice system. In the absence of institutions guaranteeing justice and law in a country, the restoration of punitive psychiatry is a matter of circumstances, a question of political necessity.

In the last ten to twelve years, elements of punitive psychiatry have appeared every so often in Russia. These have been attempts by local and regional authorities to revert to this time-tested Soviet method of solving problems. However, in each instance, as soon as the case was made public and caught the attention of the IPA, the media, and the public, the authorities have backed down.

People who have served time for their political activity in both prisons and psychiatric institutions prefer the former to the latter. At least in prison a convict has a set term to serve, whereas in a mental institution, there are no terms.

The case of “Bolotnaya” prisoner Mikhail Kosenko became the first instance of the post-Soviet regime deciding to openly and deliberately use psychiatry for political purposes.

On October 8, Moscow’s Zamoskvoretski district court sentenced Mikhail Kosenko to compulsory psychiatric treatment after recognizing his active involvement in the so-called riots that took place on May 6, 2012, on Bolotnaya Square in Moscow. Amnesty International declared Kosenko a prisoner of conscience. Kosenko’s persecution has been purely politically motivated. According to independent experts, the evaluation of Kosenko by forensic psychiatrists from the Serbsky Institute was falsified; Russia’s state forensic medical center adjusted Kosenko’s diagnosis to justify the accusations against him. Court proceedings were held in a clearly accusatory atmosphere, and Judge Ludmila Moskalenko demonstrated her total indifference to establishing the truth. All three preconditions of punitive psychiatry were met, with no reaction from government institutions, which are supposed to ensure the rule of law and justice.

The public reaction to Kosenko’s sentence was rather furious. Not only members of the opposition movement, but also the media, psychiatrists, and even those normally uninterested in politics began talking about this return to punitive psychiatry. There are obvious similarities between Kosenko’s case and the practice of psychiatric repressions against dissidents in the Soviet Union.

Just like they used to do in Soviet times, medical officials have claimed that Kosenko will be better off in a mental hospital than in prison. In her interview with REN TV, Tatyana Klimenko, aide to the health minister, listed off the advantages Mikhail Kosenko will enjoy in a mental institution: “Clean linens, clean bed, and three meals per day.”

Those who are not acquainted with the Russian penitentiary system might be puzzled by the fact that Kosenko was relieved of criminal responsibility and had his prison term replaced with an indefinite term of detention in a psychiatric institution. The widespread belief is that being in a hospital is better than being in prison; however, people who have served time for their political activity in both prisons and psychiatric institutions prefer the former to the latter. At least in prison a convict has a set term to serve, whereas in a mental institution, there are no terms. “Patients” of psychiatric hospitals are deprived of any rights and are completely at the mercy of medical personnel, who are sometimes worse than prison staff.

Once a year, a psychiatric institution’s committee of physicians can refer a patient to a judge with the request to annul compulsory treatment. The committee can also choose not to do this. It all depends on the patient’s behavior, his compliance, his ability to pay a bribe, and — in political cases — on the decisions of law enforcement officials. People can be subjected to forced psychiatric treatment for years.

The return of methods of punitive psychiatry to Russia will likely not go unnoticed by the international psychiatric community. Although it’s an unpleasant subject, the World Psychiatric Association will be compelled to deal with it again. The psychiatric community will have to denounce new cases of psychiatric abuse if it does not want to face the escalation of psychiatric repressions in Russia.

= = =

“Twenty years ago, we farewelled to the Red Empire with damnations and tears. Today, we can take a look at the recent history with calm, as if it were a historic experience. It is important because the debate on socialism has not been settled. A new generation has grown up that has a different worldview; but many young people still read Marx and Lenin. Stalin museums are opening up in the Russian cities, Stalin monuments are being erected. The Red Empire no longer exists, but the Red Man has been preserved. He lasts.”

— Nobel Lecture by Svetlana Aleksiévitch (transl.)

Trending