CCRD s. 7 (Annotated)

| Authors: | Graham Garton |

| Publisher: | Justice Canada |

| Last update: | 2004-07-01 |

| URL: | http://canlii.ca/t/t32ksk |

| Citation: | Graham Garton, The Canadian Charter of Rights Decisions Digest, Justice Canada, Updated: April 2005 (CanLII), <http://canlii.org/en/commentary/charterDigest/>. |

SECTION 7

7. Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.

Updated: July 2004

OVERVIEW

Where a court is

called upon to determine whether s. 7 has been infringed, the analysis consists

of three main stages. The first question is whether there exists a real or

imminent deprivation of life, liberty, security of the person, or a combination

of these interests. The second stage involves identifying and defining the

relevant principle or principles of fundamental justice. Finally, it must be

determined whether the deprivation has occurred in accordance with the relevant

principle or principles. Section 7 mandates a contextual analysis, which

involves a balance. Each principle of fundamental justice must be interpreted

in light of those other individual and societal interests that are of

sufficient importance that they may appropriately be characterized as

principles of fundamental justice in Canadian society: R. v. White,

[1999] 2 S.C.R. 417; Blencoe v. B.C. (Human Rights Commission), [2000] 2

S.C.R. 307, 2000 SCC 44.

The restrictions

that s. 7 is concerned with are those that occur as a result of an individual’s

interaction with the justice system and its administration (New Brunswick

(Minister of Health and Community Services) v. G.(J.), [1999] 3 S.C.R. 46.

Section 7 does not include property or economic rights, except perhaps those

fundamental to human life or survival (Irwin Toy Ltd. v. Quebec (Attorney

General), [1989] 1 S.C.R. 927; Gosselin v. Quebec (Attorney General),

[2002] 4 S.C.R. 429, 2002 SCC 84). Nevertheless, while the “liberty”

it protects is not unconstrained freedom, it is more than mere freedom from

physical restraint: B.(R.) v. Children’s Aid Society, [1995] 1 S.C.R.

315. Section 7 can extend beyond the penal context, at least where there is

“state action which directly engages the justice system and its

administration (Blencoe v. B.C. (Human Rights Commission), supra).

Further, the right to security of the person protects both the physical and

psychological integrity of the individual, but does not extend to the ordinary

stresses and anxieties that a person of reasonable sensibility would suffer as

a result of government action (New Brunswick (Minister of Health and

Community Services) v. G.(J.), supra).

The “principles

of fundamental justice” are not a protected interest, but rather a

qualifier of the right not to be deprived of life, liberty and security of the

person. As a qualifier, the phrase serves to establish the parameters of the

interests but it cannot be interpreted so narrowly as to frustrate or stultify

them (Reference re S. 94(2) Motor Vehicle Act, [1985] 2 S.C.R. 486). A

mere common law rule does not suffice to constitute a principle of fundamental

justice; rather, as the term implies, principles on which there is some

consensus that they are vital or fundamental to our societal notion of justice

are required. Principles of fundamental justice must not, however, be so broad

as to be no more than vague generalizations about what our society considers to

be ethical or moral. They must be capable of being identified with some

precision and applied to situations in a manner which yields an understandable

result: Rodriguez v. British Columbia (Attorney General), [1993] 3

S.C.R. 519. The inquiry into the principles of fundamental justice is informed

not only by Canadian experience and jurisprudence, but also by international

law, including jus cogens: Suresh v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship

and Immigration), [2002] 1 S.C.R. 3, 2002 SCC 1.

Section 7 may, in

certain contexts, provide residual protection to the interests protected by

specific provisions of the Charter. It does so in the case of s. 11(c) which

protects a person charged from being compelled to be a witness in proceedings

against that person and s. 13 which protects a witness against

self-incrimination, but s. 7 does not give an absolute right to silence or a

generalized right against self-incrimination on the American model: Thomson

Newspapers Ltd. v. Canada, [1990] 1 S.C.R. 425; R. v. Brown, [2002]

2 S.C.R. 185, 2002 SCC 32. The principle against self-incrimination is not

absolute and may reflect different rules in different contexts: R. v. S.

(R.J.), [1995] 1 S.C.R. 451.

CHARTER

DECISIONS

Headings used in

this section:

[6] “Principles

of Fundamental Justice”

[6.A] Nature and

Sources of the “Principles”

[6.D] Vagueness and

Overbreadth of Statutory Language

[6.F] Exclusion of

Evidence Obtained Abroad

[7] Property and

Economic Rights

[8] Civil Causes of

Action and Procedure.

[9] Disclosure and

Discovery in Criminal Cases

[10] Pre-Charge and

Appellate Delay

[11] Right to

Competent Counsel / Right to Counsel at State’s Expense

[12] Access to

Wiretap Packets

[13] Right to Remain

Silent / Self-Incrimination

[14] Relationship

With Sections 8-14

[1] Scope of the Guarantee

There is no longer

any doubt that s. 7 of the Charter is not confined to the penal context.

Section 7 can extend beyond the sphere of criminal law, at least where there is

“state action which directly engages the justice system and its

administration.” If a case arises in the human rights context which, on

its facts, meets the usual s. 7 threshold requirements, there is no specific

bar against such a claim and s. 7 may be engaged. The question to be addressed,

however, is not whether delays in human rights proceedings can engage s.

7 of the Charter but rather, whether the respondent’s s. 7 rights were actually

enegaged by delays in the circumstances of this case. Various parties in this

case seem to have conflated the delay issue with the threshold s. 7 issue.

However, whether the respondent’s s. 7 rights to life, liberty and security of

the person are engaged is a separate issue from whether the delay itself was

unreasonable. Before it is even possible to address the issue of whether the

respondent’s s. 7 rights were infringed in a manner not in accordance with the

principles of fundamental justice, one must first establish that the interest

in respect of which the respondent asserted his claim falls within the ambit of

s. 7. These two steps in the s. 7 analysis have been set out by La Forest J. in

R. v. Beare, as follows: ” to trigger its operation there must first be a

finding that there has been a deprivation of the right to “life, liberty

and security of the person” and, secondly, that the deprivation is contrary

to the principles of fundamental justice.” Thus, if no interest in the

respondent’s life, liberty or security of the person is implicated, the s. 7

analysis stops there. In this case, McEachern C.J.B.C. collapsed the s. 7

interests of “liberty” and security of the person” into a single

right protecting a person’s dignity against the stigma of undue, prolonged

humiliation and public degradation of the kind suffered by the respondent. In

addressing the issue of whether the respondent’s s. 7 rights have been breached

in this case, I prefer to keep the interests protected by s. 7 analytically

distinct to the extent possible. The Charter and the rights it guarantees are

inextricably bound to concepts of human dignity. This does not mean, however,

that dignity is elevated to a free-standing constitutional right protected by

s. 7 of the Charter. The notion of “dignity” in the decisions of this

Court is better understood not as an autonomous Charter right, but rather, as

an underlying value. According to the respondent, in this case, the human

dignity of a person is closely tied to a person’s reputation and privacy

interests. While this Court found in Hill v. Church of Scientology of Toronto

that reputation was a concept underlying Charter rights, it too is not an

independent Charter right in and of itself. Respect for a person’s reputation,

like respect for dignity of the person, is a value that underlies the Charter.

These two values do not support the respondent’s proposition that protection of

reputation or freedom from the stigma associated with human rights complaints

are independent constitutional s. 7 rights. I would agree with the following

passage from Reference re ss. 193 and 195.1(1) (c ) of the Criminal Code, wherein Lamer J. cautioned:

“If liberty or security of a person under s. 7 of the Charter were defined

in terms of attributes such as dignity, self-worth and emotional well-being, it

seems that liberty under s. 7 would be all inclusive. In such a state of

affairs there would be serious reason to question the independent existence in

the Charter of other rights and freedoms such as freedom of religion and

conscience or freedom of expression”. Blencoe v. B.C. (Human Rights

Commission), [2000] 2 S.C.R. 307, 2000 SCC 44.

In United States

v. Burns, nothing in our s. 7 analysis turned on the fact that the case

arose in the context of extradition rather than refoulement. Rather, the

governing principle was a general one — namely, that the guarantee of

fundamental justice applies even to deprivations of life, liberty or security

effected by actors other than our government, if there is a sufficient causal

connection between our government’s participation and the deprivation

ultimately effected. We reaffirm that principle here. At least where Canada’s

participation is a necessary precondition for the deprivation and where the

deprivation is an entirely foreseeable consequence of Canada’s participation,

the government does not avoid the guarantee of fundamental justice merely

because the deprivation in question would be effected by someone else’s hand.

We therefore disagree with the Court of Appeal’s suggestion that, in expelling

a refugee to a risk of torture, Canada acts only as an “involuntary

intermediary”. Without Canada’s action, there would be no risk of torture.

Accordingly, we cannot pretend that Canada is merely a passive participant.

That is not to say, of course, that any action by Canada that results in

a person being tortured or put to death would violate s. 7. There is always the

question, as there is in this case, of whether there is a sufficient

connection between Canada’s action and the deprivation of life, liberty, or

security: Suresh v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration),

[2002] 1 S.C.R. 3, 2002 SCC 1.

In this case, the

appellant argues that the right to a level of social assistance sufficient to

meet basic needs falls within s. 7. Can s. 7 apply to protect rights or

interests wholly unconnected to the administration of justice? The question

remains unanswered. Even if s. 7 could be read to encompass economic rights, a

further hurdle emerges. Section 7 speaks of the right not to be deprived

of life, liberty and security of the person, except in accordance with the

principles of fundamental justice. Nothing in the jurisprudence thus far

suggests that s. 7 places a positive obligation on the state to ensure that

each person enjoys life, liberty or security of the person. Rather, s. 7 has

been interpreted as restricting the state’s ability to deprive people of

these. Such a deprivation does not exist in the case at bar. One day s. 7 may

be interpreted to include positive obligations. It would be a mistake to regard

s. 7 as frozen, or its content as having been exhaustively defined in previous

cases. The question therefore is not whether s. 7 has ever been — or will ever

be — recognized as creating positive rights. Rather, the question is whether

the present circumstances warrant a novel application of s. 7 as the basis for

a positive state obligation to guarantee adequate living standards. I conclude

that they do not. I leave open the possibility that a positive obligation to

sustain life, liberty, or security of person may be made out in special

circumstances. However, this is not such a case : Gosselin v. Quebec

(Attorney General), [2002] 4 S.C.R. 429, 2002 SCC 84.

[2]

“Everyone”

Read as a whole, it

appears that s. 7 was intended to confer protection on a singularly human

level. A plain, common sense reading of the phrase “Everyone has the right

to life, liberty and security of the person” serves to underline the human

element involved; only human beings can enjoy these rights.

“Everyone” then, must be read in light of the rest of the section and

defined to exclude corporations and other artificial entities incapable of

enjoying life, liberty or security of the person, and include only human

beings. In this regard, the case of R. v. Big M Drug Mart Ltd., [1985] 1

S.C.R. 295 is of no application. There are no penal proceedings pending in this

case, so the principle articulated in Big M Drug Mart is not involved: Irwin

Toy Ltd. v. A. G. Que., [1989] 1 S.C.R. 927; Dywidag Systems v. Zutphen

Brothers Construction Ltd., [1990] 1 S.C.R. 705; Thomson Newspapers Ltd.

v. Canada, [1990] 1 S.C.R. 425; British Columbia Securities Commission

v. Branch, [1995] 2 S.C.R. 3.

The minor

differences in wording between s.7 of the Charter and s.1(a) of the Canadian

Bill of Rights provide no scope for a successful argument that Parliament

intended to extend, in the Charter, the guaranteed rights to a wider, and

different, category of species than those recognized in the Canadian Bill of

Rights. A foetus has never been recognized as a legal person, and the mere

fact that rights set out in the Charter are now guaranteed does not permit the

inference that Parliament intended to include foetuses in the term

“everyone”: Borowski v. A.G. Canada et al. (1984), 8 C.C.C. (3d) 392 (Sask. Q.B.); appeal

dismissed, (1987), 33 C.C.C. (3d) 402 (Sask. C.A.); appeal dismissed as moot

[1989] 1 S.C.R. 342.

The term

“everyone” includes every human being who is physically present in

Canada and by virtue of such presence amenable to Canadian law: Singh et al.

v. Minister of Employment and Immigration, [1985] 1 S.C.R. 177.

[3]

“Life”

The appellant argues

that, by prohibiting anyone from assisting her to end her life when her illness

has rendered her incapable of terminating her life without such assistance, by

threat of criminal sanction, s. 241(b) of the Criminal Code deprives her

of both her liberty and her security of the person. A consideration of these

interests cannot be divorced from the sanctity of life, which is one of the

three Charter values protected by s. 7. The fact that it is the criminal

prohibition in s. 241(b) which has the effect of depriving the appellant of the

ability to end her life when she is no longer able to do so without assistance

is a sufficient interaction with the justice system to engage the provisions of

s. 7: Rodriguez v. British Columbia (Attorney General), [1993] 3 S.C.R.

519.

[4]

“Liberty”

The appellants in

this case submitted that the challenged law violates their right under s. 7 to

pursue a lawful occupation. Additionally, they submitted that it restricts

their freedom of movement by preventing them from pursuing their chosen

profession in a certain location, namely, the Town of Winkler. However, as a

brief review of this Court’s Charter jurisprudence makes clear, the

rights asserted by the appellants do not fall within the meaning of s. 7. The

right to life, liberty and security of the person encompasses fundamental life

choices, not pure economic interests. As La Forest J. explained in Godbout

v. Longueuil (City): “. . . the autonomy protected by the s. 7 right to

liberty encompasses only those matters that can properly be characterized as

fundamentally or inherently personal such that, by their very nature, they

implicate basic choices going to the core of what it means to enjoy individual

dignity and independence”: Siemens v. Manitoba (Attorney General),

[2003] 1 S.C.R. 6, 2003 SCC 3.

Liberty means more

than freedom from physical restraint. It includes the right to an irreducible

sphere of personal autonomy wherein individuals may make inherently private

choices free from state interference. This is true only to the extent that such

matters “can properly be characterized as fundamentally or inherently

personal such that, by their very nature, they implicate basic choices going to

the core of what it means to enjoy individual dignity and independence”: Godbout

v. Longueuil (City). While we accept Malmo-Levine’s statement that smoking

marihuana is central to his lifestyle, the Constitution cannot be stretched to

afford protection to whatever activity an individual chooses to define as

central to his or her lifestyle: R. v. Malmo-Levine; R. v. Caine, [2003]

3 S.C.R. 571, 2003 SCC 74.

The fingerprinting

requirements of the Identification of Criminals Act infringe the rights

guaranteed by s. 7 because they require a person to appear at a specific time

and place and oblige that person to go through an identification process on

pain of imprisonment for failure to comply. However, where there is reasonable

and probable cause to believe that a person has committed an offence, it cannot

be seriously argued that subjecting a person to these procedures violates the

principles of fundamental justice: Beare v. R., [1988] 2 S.C.R. 387.

The appellant in

this case contends that the 1986 amendment to the Parole Act changing

the conditions for release on mandatory supervision amount to a denial of his

liberty contrary to the principles of fundamental justice. The respondent’s

argument that because the appellant was sentenced to twelve years’ imprisonment

there can be no further impeachment of his liberty interest within the

twelve-year period runs counter to previous pronouncements, and oversimplifies

the concept of liberty. This and other courts have recognized that there are

different types of liberty interests in the context of correctional law. In Dumas

v. LeClerc Institute, [1986] 2 S.C.R. 459, Lamer J. identified three

different deprivations of liberty: (1) the initial deprivation of liberty; (2)

a substantial change in conditions amounting to a further deprivation of

liberty; and (3) a continuation of the deprivation of liberty. In R. v.

Gamble, [1988] 2 S.C.R. 595, this Court held by a majority that the liberty

interest involved in not continuing the period of parole ineligibility may be

protected by s. 7 of the Charter. Here, the manner in which the

appellant may serve a part of his sentence, the second liberty interest

identified in Dumas, has been affected. One has “more”

liberty, or a better quality of liberty, when one is serving time on mandatory

supervision than when one is serving time in prison: Cunningham v. Canada,

[1993] 2 S.C.R. 143.

The appellants in

this case claim that parents have the right to choose medical treatment for

their infant, relying for this contention on s. 7 of the Charter, and more precisely

on the liberty interest. They assert that the right enures in the family as an

entity, basing this argument on statements made by American courts in the

definition of liberty under their Constitution. While American experience may

be useful in defining the scope of the liberty interest protected under our

Constitution, s. 7 of the Charter does not afford protection to the integrity

of the family unit as such. The Charter, and s. 7 in particular, protects

individuals. Liberty does not mean unconstrained freedom. Freedom of the

individual to do what he or she wishes must, in any organized society, be

subjected to numerous constraints for the common good. The state undoubtedly

has the right to impose many types of restraints on individual behaviour, and

not all limitations will attract Charter scrutiny. On the other hand, liberty

does not mean mere freedom from physical restraint. In a free and democratic

society, the individual must be left room for personal autonomy to live his or

her own life and to make decisions that are of fundamental personal importance.

However, a majority of the Supreme Court of Canada in this case could not agree

on whether the appellants had been deprived of their liberty when the

Children’s Aid Society was granted wardship of their daughter on the basis that

she was a “child in need of protection” within the meaning of the Ontario Child

Welfare Act: B. (R.) v. Children’s Aid Society, [1995] 1 S.C.R. 315.

It is germane to

observe that the liberty interest may be engaged although there is no

coincident deprivation in respect of the other s. 7 interests, life or security

of the person. Moreover, not every restriction on absolute freedom constitutes

a deprivation of liberty for s. 7: R. v. S. (R.J.), [1995] 1 S.C.R. 451.

The liberty interest

is engaged at the point of testimonial compulsion. Once it is engaged, the

investigation then becomes whether or not there has been a deprivation of this

interest in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice: British

Columbia Securities Commission v. Branch, [1995] 2 S.C.R. 3; Application

under s. 83.28 of the Criminal Code (Re), 2004 SCC 42.

In this case, it is

beyond doubt that the appellant’s s. 7 liberty interest is engaged by the

introduction of statutorily compelled information at his trial for the offences

against s. 239 of the Income Tax Act, owing to the threat of

imprisonment on conviction: R. v. Jarvis, [2002] 3 S.C.R. 757, 2002 SCC

73.

The weight of

judicial authority is firmly against the conclusion that the right to drive is

a liberty within the meaning of s. 7 of the Charter: Horsefield v. Ontario,

(1999), 172 D.L.R. (4th) 43 (Ont. C.A.); Buhlers v. British

Columbia, (1999), 170 D.L.R. (4th) 344 (B.C.C.A.).

A grievor under the Public

Service Staff Relations Act, even where discharge as a result of alleged

misconduct is in issue, is not a person charged with an offence nor is the

life, liberty or security of the person at stake: Forgie v. Public Service

Staff Relations Board, (1987), 32 C.R.R. 191 (F.C.A.).

The s. 7 right to

liberty does not encompass a constitutional right to practice one’s profession,

hence a provincial regulation providing for the mandatory revocation of a

physician’s licence for sexual abuse of a patient is not open to challenge

under s. 7: Mussani v. College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario, (2003),

226 D.L.R.(4th) 511, 64 O.R.(3d) 641 (Ont. Div. Ct.).

The question of what

liberties are included in s. 7 was broached by Lamer J. in Reference re Criminal Code (Man.), [1990] 1 S.C.R.

1123. The other members of the majority did not find it necessary to deal with

the precise question with which Lamer J. dealt extensively. It is a complete

theory of s. 7, the only one which has been authoritatively put forth thus far.

It attempts to unite the perspectives of the protected triad of rights

(“life, liberty and the security of the person”) and of the

principles of fundamental justice, since it enunciates “the kind of life, liberty

and security of the person sought to be protected through the principles of

fundamental justice”. It is also in accord with the previous approaches to

the issue by the Supreme Court. As well, it avoids the pitfalls of judicial

interference in general public policy. It may or may not come to represent the

final judicial statement of the meaning of s. 7, but any eventual judicial

synthesis will likely be an approximation of Lamer J.’s view. Accordingly, s. 7

is implicated when physical liberty is restricted in any circumstances, when

control over mental or physical integrity is exercised, or when the threat of

punishment is invoked for non-compliance. There is nothing of that kind, or

within striking distance of it, on the facts of the case at bar. The Appellants

say only that the filing of a certificate invoking absolute privilege under s.

39 of the Canada Evidence Act deprives them of the “liberty ”

of having an administrative decision reviewed and controlled by the courts.

However, the jurisprudence shows that such a right can be precluded entirely

except as to jurisdiction, where the executive branch is involved, even when

fairness itself is at stake: Canadian Association of Regulated Importers v.

A.G. Canada, [1992] 2 F.C. 130 (F.C.A.); leave to appeal refused

(S.C.C., June 25, 1992).

As Lamer J. points

out in Re ss. 193 and 195.1 of the Criminal Code, supra, the

restrictions on liberty that s. 7 is concerned with are those that occur as a

result of an individual’s interaction with the justice system and its

administration. He goes on to state that the rights under s. 7 do not extend to

the right to exercise a chosen profession. The trial judge dismissed the

statement by Lamer J. because the profession under consideration in that case

was prostitution. However, his words apply equally to the accounting or any

other profession. Accordingly, this Court must conclude that the restriction in

s-s. 14(1) of the Public Accounting and Auditing Act limiting the right

to practice that profession does not engage s. 7 of the Charter: Government

of P.E.I. v. Walker, (1993), 107 D.L.R. (4th) 69 (P.E.I.C.A.); appeal

dismissed, [1995] 2 S.C.R. 407 (S.C.C.).

Although the Supreme

Court, in Chiarelli v. M.E.I., infra, in deciding the issue on the basis

of fundamental justice, left open the question whether deportation for serious

offences can be conceptualized as a deprivation of liberty under s. 7, this

Court has already decided that it cannot, and is bound by its previous

decisions: Canepa v. M.E.I., [1992] 3 F.C., 270 (F.C.A.); Barrera v.

Canada (M.E.I.), [1993] 2 F.C. 3 (F.C.A.).

Section 7 deals with

individual rights, not collective rights such as the right of union members to

strike. In the context of the negotiation of a labour agreement, the individual

rights of the members of a union are exercised, discussed and expanded in a

collective process which, by necessity, is subject to a set of different rules

to ensure its proper functioning. The individual members delegate the exercise

of their rights to a collective bargaining unit with the possibility, if need

be, of resorting to a collective action such as a strike. The trial judge was

right in his conclusion that the Maintenance of Ports Operations Act did

not violate s. 7 by reason that it prohibited the appellants from taking strike

action, be it in the form of collectively refusing to resume work pursuant to

the cessation of the lockout or going on a strike proper at a later date. In

the B.C. Motor Vehicle Act Reference, Lamer J. viewed s. 7 as protecting

interests “that are properly and have been traditionally within the domain

of the judiciary… The common thread that runs throughout s. 7 and ss. 8-14 is

the involvement of the judicial branch as guardian of the justice system”.

The right to strike and the right of Parliament to curtail it in the public

interest in appropriate circumstances have never been traditionally within the

domain of the judiciary. Here, the back-to-work legislation involved important

social, political and economical considerations with national and international

ramifications which were never intended to be discussed under the right to

individual liberty found in s. 7. The appellants are trying to do under s. 7,

i.e., under the cover of the right to liberty, what they cannot do under s. 2(d),

i.e., under freedom of association: I.L.W.U. v. The Queen, [1992] 3 F.C.

758, (F.C.A.); appeal dismissed, [1994] 1 S.C.R. 150.

[5]

“Security of the Person”

This Court has held

on a number of occasions that the right to security of the person protects “both

the physical and psychological integrity of the individual”. Although these

cases considered the right to security of the person in a criminal law context,

I believe that the protection accorded by this right extends beyond the

criminal law and can be engaged in child protection proceedings. It is clear

that the right to security of the person does not protect the individual from

the ordinary stresses and anxieties that a person of reasonable sensibility

would suffer as a result of government action. For a restriction of security of

the person to be made out, the impugned state action must have a serious and

profound effect on a person’s psychological integrity. The effects of the state

interference must be assessed objectively, with a view to their impact on the

psychological integrity of a person of reasonable sensibility. This need not

rise to the level of nervous shock or psychiatric illness, but must be greater

than ordinary stress or anxiety. I have little doubt that state removal of a

child from parental custody pursuant to the state’s parens patriae

jurisdiction constitutes a serious interference with the psychological

integrity of the parent. Not every state action which interferes with the

parent-child relationship will restrict a parent’s right to security of the

person. For example, a parent’s security of the person is not restricted when,

without more, his or her child is sentenced to jail or conscripted into the

army. Nor is it restricted when the child is negligently shot and killed by a

police officer. While the parent may suffer significant stress and anxiety as a

result of the interference with the relationship occasioned by these actions,

the quality of the “injury” to the parent is distinguishable from that in the

present case. In the aforementioned examples, the state is making no pronouncement

as to the parent’s fitness or parental status, nor is it usurping the parental

role or prying into the intimacies of the relationship. In short, the state is

not directly interfering with the psychological integrity of the parent qua

parent. In both Reference re ss. 193 and 195.1(c) of the Criminal Code

and B.(R.), supra, I held that the restrictions on liberty and security

of the person that s. 7 is concerned with are those that occur as a result of

an individual’s interaction with the justice system and its administration. A

child custody application is an example of state action which directly engages

the justice system and its administration. The Family Services Act

provides that a judicial hearing must be held in order to determine whether a

parent should be relieved of custody of his or her child: New Brunswick

(Minister of Health and Community Services) v. G.(J.), [1999] 3 S.C.R. 46; Winnipeg

Child and Family Services v. K.L.W., [2000] 2 S.C.R. 519, 2000 SCC

48.

Not all state

interference with an individual’s psychological integrity will engage s. 7.

Where the psychological integrity of a person is at issue, security of the

person is restricted to “serious state-imposed psychological stress”

(Dickson C.J. in Morgentaler). The words “serious state-imposed

psychological stress” delineate two requirements that must be met in order

for security of the person to be triggered. First, the psychological harm must

be state imposed, meaning that the harm must result from the actions of

the state. Second the psychological prejudice must be serious. Not all

forms of psychological prejudice caused by government will lead to automatic s.

7 violations. Stress, anxiety and stigma may arise from any criminal trial,

human rights allegations, or ever a civil action, regardless of whether the

trial or process occurs within a reasonable time. We are therefore not

concerned in this case with all such prejudice but only that impairment which

can be said to flow from the delay in the human rights process. It would be

inappropriate to hold government accountable for harms that are brought about

by third parties who are not in any sense acting as agents of the state. It is

only in exceptional cases where the state interferes in profoundly intimate and

personal choices of an individual that state-caused delay in human rights

proceedings could trigger the s. 7 security of the person interest. While these

fundamental personal choices would include the right to make decisions

concerning one’s body free from state interference or the prospect of losing

guardianship of one’s children, they would not easily include the type of

stress, anxiety and stigma that results from administrative or civil

proceedings. The majority of the Court of Appeal in the case at bar erred in

transplanting s. 11(b) principles set out in the criminal law context to human

rights proceedings under s. 7. The effect of the Court of Appeal’s decision was

to extract an element of s. 11(b) – the element of stigma, which may be

sufficient in the context of criminal proceedings and s. 11(b), to create a

deprivation of the security of the person – and apply it to a process that

differs with respect to objectives, consequences and procedures. As this Court

has recently confirmed in Mills (1999), Charter rights must be

interpreted and defined in a contextual manner, because they often inform, and

are informed by, other similarly deserving rights and values at play in

particular circumstances. The Court of Appeal has failed to examine the rights

protected by s. 7 in the context of this case. I do not doubt that parties in

human rights sex discrimination proceedings experience some level of stress and

disruption of their lives as a consequence of allegations of complainants. Even

accepting that the stress and anxiety experienced by the respondent in this

case was linked to delays in the proceedings, I cannot conclude that the scope

of his security of the person protected by s. 7 of the Charter covers

such emotional effects nor that they can be equated with the kind of stigma contemplated

in Mills (1986), of an overlong and vexatious pending criminal trial or

in G.(J.), where the state sought to remove a child from his or her parents. If

the purpose of the impugned proceedings is to provide a vehicle or acts as an

arbiter for redressing private rights, some amount of stress and stigma

attached to the proceedings must be accepted. My conclusion that the respondent

is unable to cross the first threshold of the s. 7 Charter analysis in

the circumstances of this case should not be construed as a holding that

state-caused delays in human rights proceedings can never trigger an

individual’s s. 7 rights. It may well be that s. 7 rights can be engaged by a

human rights process in a particular case. Blencoe v. B.C. (Human Rights

Commission), [2000] 2 S.C.R. 307, 2000 SCC 44.

Prosecution for an

absolute liability offence under the Highway Traffic Act, for which the penalty

may be a significant fine, does not engage the kind of exceptional

state-induced psychological stress that would trigger the security of the

person guarantee: R. v. 1260448 Ont. Inc., (2003), 180

C.C.C.(3d) 254 (Ont. C.A.).

The appellant

submits that the surreptitious recording of his voice by the police for voice

identification purposes violated his right to security of the person. The

taking of the voice sample was insubstantial, of very short duration and left

no lasting impression. There was no penetration of the appellant’s body and no

substance removed from it. In R. v. Parsons this court held that the

surreptitious videotaping of an accused in police custody for purposes of

preparing a photo identification line-up did not constitute a s. 7 violation.

We see no meaningful distinction between that case and the one at hand: R.

v. Pelland, (1997), 99 O.A.C. 62 (Ont. C.A.).

In the present case,

the provincial Environmental Quality Act imposes a minimum fine upon

conviction regardless of capacity to pay. Immediate imprisonment is a real

possibility under s. 237 of the Code of

Civil Procedure if the sentencing judge is satisfied that the defendant

will abscond, and s. 347 contemplates imprisonment in default of payment if the

justice believes that no other method provided in the Code will be effective in

recovering the fine. The combined effect of these provisions appears to impair

the right to liberty of the defendants in a meaningful rather than an

insignificant way, and they may therefore invoke s. 7 of the Charter in order

to challenge the constitutional validity of the law under which they are

charged: Québec v. Enterprises M.G. de Guy Ltée, (1996), 107 C.C.C. (3d)

1 (Qué. C.A.).

There is no question

that personal autonomy, at least with respect to the right to make choices

concerning one’s own body, control over one’s physical and psychological

integrity, and basic human dignity are encompassed within security of the

person, at least to the extent of freedom from criminal prohibitions which

interfere with these. The effect of the prohibition in s. 241(b) of the Criminal

Code is to prevent the appellant from having assistance to commit suicide

when she is no longer able to do so on her own. That there is a right to choose

how one’s body will be dealt with, even in the context of beneficial medical

treatment, has long been recognized by the common law. To impose medical

treatment on one who refuses it constitutes battery, and our common law has

recognized the right to demand that medical treatment which would extend life

be withheld or withdrawn. These considerations lead to the conclusion that the

prohibition in s. 241(b) deprives the appellant of autonomy over her person and

causes her physical pain and psychological stress is a manner which impinges on

the security of the person: Rodriguez v. British Columbia (Attorney General),

[1993] 3 S.C.R. 519.

Although the

question of economic rights fundamental to survival is an open one in the

Supreme Court of Canada, it has been considered by courts below that level.

Those courts have generally held that there is no right under s. 7 to social

assistance, nor to a minimum standard of living. In a number of the decisions

denying violation of s. 7 the courts have approved statements made by Professor

Hogg in Constitutional Law of Canada. There, Professor Hogg considered

the argument that “security of the person” in s. 7 included the

economic capacity to satisfy basic human needs. He considered the possible role

of the courts in dealing with such an argument and made the following

statement: “The suggested role also involves a massive expansion of

judicial review, since it would bring under judicial scrutiny all of the

elements of the modern welfare state, including the regulation of trades and

professions, the adequacy of labour standards and bankruptcy laws and, of

course, the level of public expenditures on social programs. As Oliver Wendell

Holmes would have pointed out, these are the issues upon which elections are

won and lost; the judges need a clear mandate to enter that arena, and s. 7

does not provide that clear mandate”: Masse et al. v. Ontario (Ministry

of Community and Social Services), (1996), 134 D.L.R. (4th) 20 (Ont. Div.

Ct.); leave to appeal refused (Ont. C.A., April 30, 1996); leave to appeal

refused (S.C.C., December 5, 1996).

A commission of

inquiry appointed by order-in-council is a recommendatory, not an adjudicative,

body. It will make no determinations as to guilt or innocence or civil or

criminal liability. Nor will its report necessarily lead to any subsequent

proceedings against anyone. That being so, it cannot be said that the inquiry

will deprive any person of liberty or security of the person: Robinson et

al. v. The Queen et al., (1986), 28 C.C.C. (3d) 489 (B.C.S.C.); appeal

dismissed, [1987] 3 W.W.R. 362 (B.C.C.A.); leave to appeal refused (S.C.C.,

April 9, 1987); Re First Investors Corporation Ltd. (1988), 58 Alta. L.R. 38 (Alta. Q.B.); appeal

dismissed, (1988), 52 D.L.R. (4th) 168 (Alta. C.A.).

The appellant here submitted

that security of the person ought to encompass the right to pursue one’s

occupation or profession and not to be deprived thereof except in accordance

with fundamental justice. In order to give s.7 that interpretation, security of

the person must be interpreted to mean the economic capacity to satisfy basic

human needs, that is, to earn a living. Nowhere in s.7 is there reference to

property rights and that omission is significant: Bassett v. Government of

Canada et al., (1987), 35 D.L.R. (4th) 537 (Sask. C.A.).

A finding of

discrimination against an employer as the basis for a remedial order under the Saskatchewan

Human Rights Code does not impinge upon the employer’s right to “life,

liberty and security of the person”. To construe a compensatory order

based upon a finding of discrimination designed to relieve a victim of the

effects of discrimination as seriously hurting the body or mind of the

discriminator would be to stretch the boundaries of the concept of “life,

liberty and security of the person” well beyond the breaking point: Pasqua

Hospital et al. v. Harmatiuk, (1987), 42 D.L.R. (4th) 134 (Sask. C.A.).

To require a

penitentiary inmate to provide a specimen of urine for purposes of testing for

trace elements of intoxicants is an interference with bodily integrity and

security of the person. Urinalysis may reveal health or other conditions beyond

the indications sought for traces of unauthorized intoxicants. In many cases

requiring a specimen for testing aside from health reasons might lead to a

measure of psychological stress, particularly where, as here, the procedure for

collecting the sample involves direct observation by another. The requirement

deprives the inmate concerned of security of his or her person. To require this

or risk punishment for failure to comply with an order, is also an interference

with the liberty of the person: Jackson v. Disciplinary Tribunal, [1990]

3 F.C. 55 (F.C.T.D.).

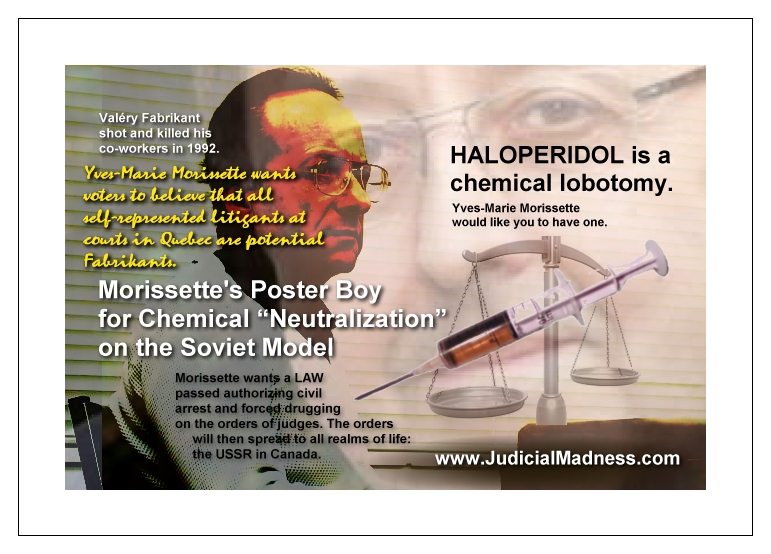

The right to

determine what shall, or shall not, be done with one’s own body, and to be free

from non-consensual medical treatment, is a right deeply rooted in our common

law. This right underlies the doctrine of informed consent. With very limited

exceptions, every person’s body is considered inviolate, and, accordingly,

every competent adult has the right to be free from unwanted medical treatment.

The fact that serious risks or consequences may result from a refusal of

medical treatment does not vitiate the right of medical self-determination. It

was contended here that the Ontario Mental Health Act, which authorizes

a review board to override an involuntary patient’s competent refusal to take

anti-psychotic drugs, as expressed by the patient through his or her

substitute, contravenes s. 7. It is manifest that the impugned provisions

operate so as to deprive the appellants of their right to security of the

person. The common law right to bodily integrity and personal autonomy is so

entrenched in the traditions of our law as to be ranked as fundamental and

deserving of the highest order of protection. Few medical procedures can be

more intrusive than the forcible injection of powerful mind altering drugs

which are often accompanied by severe and sometimes irreversible adverse side

effects. To deprive involuntary patients of any right to make competent decisions

with respect to such treatment when they become incompetent clearly infringes

their right to security of the person. A legislative scheme that permits the

competent wishes of a psychiatric patient to be overridden, and which allows a

patient’s right to personal autonomy and self-determination to be defeated,

without affording a hearing as to why the substitute consent-giver’s decision

to refuse consent based on the patient’s wishes should not be honoured violates

the basic tenets of our legal system: Fleming v. Reid, (1991), 82 D.L.R.

(4th) 298 (Ont. C.A.).

This Court has great

difficulty with a proposition that would bring a government policy decision

concerning the use of nuclear power within the scope of s. 7. The government

decided to develop atomic energy for peaceful purposes, one being to generate

electricity by the use of nuclear power. The government was well aware of the

inherent risks but, in its wisdom, proceeded with fostering the development of

nuclear reactors by enacting the Nuclear Liability Act to deal with the

economic consequences of the known risks to the public. Those policy decisions

cannot invoke s. 7 security. Further, the plaintiffs have failed to prove that

there is a greater risk to the public of producing electricity by nuclear power

than by alternate methods. It is not sufficient for the plaintiffs to allege

that there are greater possible consequences to the security of the person

because of the Act. As Dickson J. stated in Operation Dismantle:

“Section 7 of the Charter cannot reasonably be read as imposing a duty on

the government to refrain from those acts which might lead to

consequences that deprive or threaten to deprive individuals of their life and

security of the person. A duty of the federal cabinet cannot arise on the basis

of speculation and hypothesis about possible effects of government

action”: Energy Probe v. A.G. Canada, (1994), 17 O.R. (3d) 717

(Ont. Gen. Div.).

[6]

“Principles of Fundamental Justice”

[6.A]

Nature and Sources of the “Principles”

Jurisprudence on s.

7 has established that a “principle of fundamental justice” must

fulfill three criteria. First, it must be a legal principle. This serves two

purposes. First, it “provides meaningful content for the s. 7

guarantee”; second, it avoids the “adjudication of policy matters”.

Second, there must be sufficient consensus that the alleged principle is

“vital or fundamental to our societal notion of justice”. The

principles of fundamental justice are the shared assumptions upon which our

system of justice is grounded. They find their meaning in the cases and

traditions that have long detailed the basic norms for how the state deals with

its citizens. Society views them as essential to the administration of justice.

Third, the alleged principle must be capable of being identified with precision

and applied to situations in a manner that yields predictable results. Examples

of principles of fundamental justice that meet all three requirements include

the need for a guilty mind and for reasonably clear laws: Canadian

Foundation for Children, Youth and the Law v. Canada (Attorney General),

[2004] 1 S.C.R. 76, 2004 SCC 4; Application under s. 83.28 of the Criminal Code

(Re), 2004 SCC 42.

Discerning the

principles of fundamental justice with which deprivation of life, liberty or

security of the person must accord, in order to withstand constitutional

scrutiny, is not an easy task. A mere common law rule does not suffice to

constitute a principle of fundamental justice, rather, as the term implies,

principles upon which there is some consensus that they are vital or

fundamental to our societal notion of justice are required. Principles of

fundamental justice must not, however, be so broad as to be no more than vague

generalizations about what our society considers to be ethical or moral. They

must be capable of being identified with some precision and applied to

situations in a manner which yields an understandable result. They must also be

legal principles. To discern the principles of fundamental justice governing a

particular case, it is helpful to review the common law and the legislative

history of the offence in question and, in particular, the rationale behind the

practice itself (here, the continued criminalization of assisted suicide) and

the principles which underlie it. It is also appropriate to consider the state

interest. Fundamental justice requires that a fair balance be struck between

the interests of the state and those of the individual. The respect for human

dignity, while one of the underlying principles upon which our society is

based, is not a principle of fundamental justice within the meaning of s. 7.

Where the deprivation of the right in question does little or nothing to

enhance the state’s interest (whatever it may be), a breach of fundamental

justice will be made out, as the individual’s rights will have been deprived

for no valid purpose. It follows that before one can determine that a statutory

provision is contrary to fundamental justice, the relationship between the

provision and the state interest must be considered. One cannot conclude that a

particular limit is arbitrary because it bears no relation to, or is

inconsistent with, the objective that lies behind the legislation without

considering the state interest and the societal concerns which it reflects. In

the present case, given the concerns about abuse that have been expressed and

the great difficulty in creating appropriate safeguards to prevent these, it

can not be said that the blanket prohibition on assisted suicide is arbitrary

or unfair, or that it is not reflective of fundamental values at play in our

society: Rodriguez v. British Columbia (Attorney General), [1993] 3

S.C.R. 519; R. v. Ruzic, [2001] 1 S.C.R. 687, 2001 SCC 24.

The principles of

fundamental justice are not a protected interest, but rather a qualifier of the

right not to be deprived of life, liberty and security of the person. As a

qualifier, the phrase serves to establish the parameters of the interests but

it cannot be interpreted so narrowly as to frustrate or stultify them. It would

be wrong to interpret fundamental justice as being synonymous with natural

justice. To do so would strip the protected interests of much, if not most, of

their content and leave the right to life, liberty and security of the person

in a sorely emaciated state. Sections 8 to 14 of the Charter address specific

deprivations of the right to life, liberty and security of the person in breach

of the principles of fundamental justice and, as such, violations of s.7. They

are designed to protect, in a specific manner and setting, the right to life,

liberty and security of the person. It would be incongruous to interpret s.7

more narrowly than the rights in ss. 8 to 14. Whether any principle may be said

to be a principle of fundamental justice within the meaning of s.7 will rest

upon an analysis of the nature, sources, rationale and essential role of that

principle within the judicial process and in our legal system, as it evolves.

Consequently, those words cannot be given any exhaustive content or simple

enumerative definition, but will take on concrete meaning as the courts address

alleged violations of s.7. For the purposes of the present case, a law that has

the potential to convict a person who has not really done anything wrong offends

the principles of fundamental justice and, if imprisonment is available as a

penalty, such a law then violates a person’s right to liberty under s.7, i.e.,

absolute liability and imprisonment cannot be combined: Reference Re S.

94(2) Motor Vehicle Act, [1985] 2 S.C.R. 486; Vaillancourt v. R.,

[1987] 2 S.C.R. 636.

In Re B.C. Motor

Vehicle Act, Lamer J. indicated that the principles of fundamental justice

“are to be found in the basic tenets of our legal system”. To determine the

content of these “basic tenets” in any given circumstance, we must have regard

to “the applicable principles and policies that have animated legislative and

judicial practice in the field”. It is important to remember that the

legislative and judicial “principles and policies” that have so far defined the

protections granted against self-incrimination have, as is true in other areas,

sought to achieve a contextual balance between the interests of the individual

and those of society. This balancing is crucial in determining whether or not a

particular law, or in the present case state action, is inconsistent with the

principles of fundamental justice. This is all the more apparent in the instant

case, where the appellant challenges a regulatory procedure — the use

of hail reports and fishing logs — designed (and employed) in the public

interest. In evaluating the constitutionality of this procedure, we must be

careful to keep the interests of both the individual and society in mind. The

balance thus far achieved is reflected in the common law. Though it is not, of

course, determinative of rights guaranteed under s. 7, the common law does give

us a valuable indication of what is just and fair in the circumstances: R.

v. Fitzpatrick, [1995] 4 S.C.R. 1554.

We do not think that

Cunnigham, Thomson Newspapers and Rodriguez should be taken as suggesting that

courts engage in a free-standing inquiry under s. 7 into whether a particular

legislative measure “strikes the right balance” between individual

and societal interests in general, or that achieving the right balance is

itself an overarching principle of fundamental justice. Such a general

undertaking to balance individual and societal interests, independent of any

identified principle of fundamental justice, would entirely collapse the s.

1 inquiry into s. 7. The balancing of individual and societal interests within

s. 7 is only relevant when elucidating a particular principle of fundamental

justice. As Sopinka J. explained in Rodriguez, “in arriving at

these principles [of fundamental justice], a balancing of the interest of

the state and the individual is required”. Once the principle of

fundamental justice has been elucidated, however, it is not within the ambit of

s. 7 to bring into account such “societal interests” as health care

costs. For a rule or principle to constitute a principle of fundamental justice

for the purposes of s. 7, it must be a legal principle about which there is

significant societal consensus that it is fundamental to the way in which the

legal system ought fairly to operate, and it must be identified with sufficient

precision to yield a manageable standard against which to measure deprivations

of life, liberty or security of the person. Contrary to the appellants’

assertion, we do not think there is a consensus that the harm principle is the

sole justification for criminal prohibition. No doubt, the presence of

harm to others may justify legislative action under the criminal law power.

However, we do not think that the absence of proven harm creates the

unqualified barrier to legislative action that the appellants suggest. On the

contrary, the state may sometimes be justified in criminalizing conduct that is

either not harmful (in the sense contemplated by the harm principle), or that

causes harm only to the accused. A criminal law that is shown to be arbitrary

or irrational will infringe s. 7. Our colleagues LeBel and Deschamps JJ.

consider the marihuana prohibition to be disproportionate to the societal

problems at issue, and, thus arbitrary. This, we think, puts the threshold of

judicial intervention too low. Marihuana is a psychoactive drug “whose use

causes alteration of mental function” according to the trial judge. This

alteration creates a potential harm to others when the user engages in “driving,

flying and other activities involving complex machinery”. Chronic users

may suffer “serious” health problems. Vulnerable groups are at

particular risk. These findings of fact disclose a sufficient state interest to

support Parliament’s intervention should Parliament decide that it is wise to

continue to do so, subject to a constitutional standard of gross

disproportionality. If Parliament is otherwise acting within its jurisdiction

by enacting a prohibition on the use of marihuana, it does not lose that

jurisdiction just because there are other substances whose health and safety

effects could arguably justify similar legislative treatment. Parliament may,

as a matter of constitutional law, determine what is not criminal as

well as what is. The choice to use the criminal law in a particular context

does not require its use in any other. Parliament’s decision to move in one

area of public health and safety without at the same time moving in other areas

is not, on that account alone, arbitrary or irrational. R. v.

Malmo-Levine; R. v. Caine, [2003] 3 S.C.R. 571, 2003 SCC 74.

As a majority of

this Court made clear in the case of Malmo-Levine, supra, the “balancing

of interests” referred to by McLachlin J. in Cunningham is to be taken

into consideration by courts only when they are deriving or construing the

content and scope of the principles of fundamental justice themselves. It is

not in and of itself a freestanding principle of fundamental justice which must

be respected if a deprivation of life, liberty and security of the person is to

be upheld: R. v. Demers, 2004 SCC 46.

The content of the

“principles of fundamental justice” was initially explored by Lamer

J. in Re B.C. Motor Vehicle Act: “… the principles of fundamental

justice are to be found in the basic tenets of our legal system. They do

not lie in the realm of general public policy but in the inherent domain of the

judiciary as guardian of the justice system.” Lamer J. also recognized that

international law and opinion is of use to the courts in elucidating the scope

of fundamental justice. Dickson C.J. made a similar observation in Slaight

Communications. Although this particular appeal arises in the context of

Canada’s bilateral extradition arrangements with the United States, it is

properly considered in the broader context of international relations

generally, including Canada’s multilateral efforts to bring about change in

extradition arrangements where fugitives may face the death penalty, and

Canada’s advocacy at the international level of the abolition of the death

penalty itself: United States v. Burns, [2001] 1 S.C.R. 283, 2001

SCC 7.

To determine whether

the dangerous offender provisions of Part XXI of the Criminal Code violate the principles of

fundamental justice by the deprivation of liberty suffered by the offender, it

is necessary to examine Part XXI in light of the basic principles of penal

policy that have animated legislative and judicial practice in Canada and other

common law jurisdictions. It is clear that the indeterminate detention is

intended to serve both punitive and preventive purposes. Both are legitimate

aims of the criminal sanction. However, it is clear that the present Charter

inquiry is concerned also, if not primarily, with the effects of the

legislation. This requires investigating the “treatment meted out”,

i.e. what is actually done to the offender and how that is accomplished.

Whether this treatment violates constitutional precepts seems to be an issue

more aptly discussed under ss. 9 and 12, because these provisions focus on

specific manifestations of the principles of fundamental justice: Lyons v.

R., [1987] 2 S.C.R. 309.

The accused here

contended that the right to equality before the law is a principle of

fundamental justice. To find constitutional protection for the right to equality

before the law under s. 7 here would be contrary to the clear expression of

legislative intention resulting from ss. 15 and 32(2) of the Charter that the

constitutional protection of this right was not to take effect until April 17,

1985. As this Court has observed, there may be some overlap between s. 7 and

other provisions of the Charter. It would be wrong, however, in view of the

clear expression of legislative intention, to give effect to such protection as

s. 7 might otherwise afford to the right to equality before the law in a case

to which s. 15 could not apply because it was not in force at the relevant

time: Cornell v. R., [1988] 1 S.C.R. 461.

The common law

permitted a number of intrusions on the dignity of an individual or persons in

custody in the interest of law enforcement which were more serious than

fingerprinting. While the common law is not determinative in assessing whether

a particular practice violates a principle of fundamental justice, it is

certainly one of the major repositories of the basic tenets of our legal system

referred to in Re B.C. Motor Vehicle Act, supra. The common law

experience reveals that the vast majority of judges who have had to consider

the matter have not found custodial fingerprinting fundamentally unfair. Indeed

they were prepared to accept the procedure as permissible at common law and as

being similar in principle to the authority to physically restrain a person in

custody, and to physically search that person. Legislative practice has been

similar. The fact that the Act gives the police a discretion whether or

not to take fingerprints does not offend principles of fundamental justice.

Discretion is an essential feature of the criminal justice system. A system

that attempted to eliminate discretion would be unworkably complex and rigid.

If it was established that a discretion was exercised for improper or arbitrary

motives, a remedy under s. 24 of the Charter would lie, but no allegation of

this kind has been made here: Beare v. R., [1988] 2 S.C.R. 387.

This Court has previously

indicated that prosecutorial discretion is consistent with Charter requirements

of fundamental justice. The same reasons underlie the necessity for permitting

a discretion to decide whether a Canadian should be prosecuted in Canada or

abroad. As this Court observed in Beare, supra, “if, in a

particular case, it was established that a discretion was exercised for

improper or arbitrary motives, a remedy under s. 24 of the Charter would

lie”: U.S.A. v. Cotroni, [1989] 1 S.C.R. 1469; R. v.

Power, [1994] 1 S.C.R. 601; U.S.A. v. Leon, [1996] 1 S.C.R. 888.

Initially, the

“basic tenets of our legal system” must be discovered by reference to

the legal rules relating to the right which our legal system has adopted. The

right to silence asserted here has been said to be “general and abstract,

concealing a bundle of more specific legal relationships. It is only by an

analysis of the surrounding legal rules that those more precise elements of the

right can be identified.” Thus rules such as the common law confessions

rule, the privilege against self-incrimination and the right to counsel may

assist in determining the scope of a detained person’s right to silence under

s. 7. At the same time, existing common law rules may not be conclusive. It

would be wrong to assume that the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Charter

are cast forever in the straitjacket of the law as it stood in 1982. For this

reason, a fundamental principle of justice may be broader and more general than

the particular rules which exemplify it. A second reason why a fundamental

principle of justice may be broader in scope than a particular legal rule, such

as the confessions rule, is that it must be capable of embracing more than one

rule and reconciling diverse but related principles. Thus, the right of a

detained person to silence should be philosophically compatible with related

rights, such as the right against self-incrimination at trial and the right to

counsel. The final reason why a principle of fundamental justice may be broader

than a particular rule exemplifying it lies in considerations relating to the

philosophy of the Charter and the purpose of the fundamental right in question

in that context. The Charter has fundamentally changed our legal landscape. A

legal rule relevant to a fundamental right may be too narrow to be reconciled

with the philosophy and approach of the Charter and the purpose of the Charter

guarantee: R. v. Hebert, [1990] 2 S.C.R. 151.

The Charter analysis

here, because the appeal concerns a challenge to a common law, judge-made rule,

involves somewhat different considerations than would apply to a challenge to a

legislative provision. It is not strictly necessary to go on to consider the

application of s. 1 after the existing common law rule has been found to limit

the s. 7 right. It would be appropriate to consider at this stage whether an

alternative common law rule could be fashioned which would not be contrary to

the principles of fundamental justice. If it is possible to reformulate a

common law rule so that it will not conflict with the principles of fundamental

justice, such a reformulation should be undertaken: R. v. Daviault,

[1994] 3 S.C.R. 63.

The appellant, a

Convention refugee who has exhausted his domestic remedies and is to be removed

from Canada, contends that the principles of fundamental justice include the

right to remain in Canada until his international law remedies have been

exhausted. He asserts that once Canada grants an individual right, as it did by

signing the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and Protocol,

it must ensure a fair process and an effective remedy, and since his removal

would render any remedy nugatory, it must be enjoined. Canada has never

incorporated either the Covenant or the Protocol into Canadian law by implementing

legislation. Absent such legislation, neither has any legal effect in Canada.

While Canada’s international human rights obligations may inform the content of

the principles of fundamental justice, the appellant is not merely asking for

an interpretation. Instead, he seeks to use s. 7 to enforce Canada’s

international commitments in a domestic court. This he cannot do: Ahani v.

Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), (2002), 208 D.L.R.(4th) 66,

91 C.R.R.(2d) 145 (Ont. C.A.); leave to appeal refused (S.C.C., May 16, 2002).

[6.B]

Substantive Application

As discussed in R.

v. Pearson, [1992] 3 S.C.R. 665, the particular requirements of the presumption

of innocence as a substantive principle of fundamental justice will vary

according to the context in which it comes to be applied. The principle does

not necessarily require anything in the nature of proof beyond reasonable

doubt, because the particular step in the process does not involve a

determination of guilt. In this case, the provisions of Part XX.1 of the Criminal Code permit the State, through a

court or a Review Board, to deprive an accused who has been found unfit to

stand trial of his or her liberty. The appellant argues that the State cannot

subject a permanently unfit accused to the criminal charges for an

indeterminate period with only the goal of ensuring public safety, based solely

on a prima facie case that he or she committed the offence charged. In our

view, the deprivation of the unfit accused’s liberty accords with the presumption

of innocence. The Review Board proceedings under ss. 672.54 and 672.81(1) do

not involve a determination of guilt or innocence. Nor do they presume that the

unfit accused is dangerous. Section 672.33 does not presume guilt, but rather

aims at preventing abuses of the regime under Part XX.1 Cr.C. by providing that

the accused is acquitted when the evidence presented to the court is

insufficient to put him or her on trial. Even though the disposition orders do

restrict the unfit person’s liberty, they do not aim to punish the accused. Nor

are they based on a presumption of guilt or innocence. The prima facie case

against the unfit accused is sufficient to keep him or her under Part XX.1

Cr.C. and is consistent with Pearson, supra: R. v. Demers, 2004 SCC 46.

While Parliament

retains the power to define the elements of a crime, the courts now have the

jurisdiction and, more important, the duty, when called upon to do so, to

review that definition to ensure that it is in accordance with the principles

of fundamental justice. In effect, this Court’s decision in Reference Re S.

94(2) Motor Vehicle Act, supra, acknowledges that, whenever the state

resorts to the restriction of liberty, such as imprisonment, to assist in the

enforcement of a law, there is, as a principle of fundamental justice, a

minimum mental state which is an essential element of the offence. It thus

elevated mens rea from a presumed element to a constitutionally required

element. That case did not decide what level of mens rea was

constitutionally required for each type of offence, but inferentially decided

that even for a mere provincial regulatory offence at least negligence was

required, in that at least a defence of due diligence must always be open to an

accused who risks imprisonment upon conviction. It may well be that, as a

general rule, the principles of fundamental justice require proof of a

subjective mens rea with respect to the prohibited act, in order to

avoid punishing the morally innocent. However, for the purposes of this case

only, this Court will assume that something less than subjective foresight of

the result may, sometimes, suffice for the imposition of criminal liability for

causing that result through intentional criminal conduct. Whatever the minimum mens

rea for the act or the result may be, there are, though very few in number,

certain crimes where, because of the special nature of the stigma attached to a

conviction therefor or the available penalties, the principles of fundamental

justice require a mens rea reflecting the particular nature of the

crime. Such is theft, where a conviction requires proof of some dishonesty.

Murder is another such offence. The punishment for murder is the most severe in

our society and the stigma that attaches to a conviction is similarly extreme.

Murder is distinguished from manslaughter only by the mental element with

respect to the death. It is thus clear that there must be some special mental

element with respect to the death before a culpable homicide can be treated as

a murder. The special mental element gives rise to the moral blameworthiness

which justifies the stigma and sentence attached to a murder conviction. For

the sole purpose of this appeal, this Court will go no further than say that it

is a principle of fundamental justice that, absent proof beyond a reasonable

doubt of at least objective foreseeability, there surely cannot be a murder

conviction: Vaillancourt v. R., [1987] 2 S.C.R. 636; Laviolette v. R.,

[1987] 2 S.C.R. 667.

A conviction for

murder carries with it the most severe stigma and punishment of any crime in

our society. The principles of fundamental justice require, because of the

special nature of the stigma attached to a conviction for murder, and the

available penalties, a mens rea reflecting the particular nature of that

crime. The effect of s. 213 of the Criminal Code is to violate the

principle that punishment must be proportionate to the moral blameworthiness of

the offender, or the fundamental principle of a morally based system of law

that those causing harm intentionally be punished more severely than those

causing harm unintentionally. The rationale underlying the principle that

subjective foresight of death is required before a person is labelled and

punished as a murderer is linked to the more general principle that criminal

liability for a particular result is not justified except where the actor

possesses a culpable mental state in respect of that result. The stigma and

punishment attaching to the most serious of crimes, murder, should be reserved

for those who choose to intentionally cause death or who choose to inflict

bodily harm that they know is likely to cause death. The essential role of

requiring subjective foresight of death in the context of murder is to maintain

a proportionality between the stigma and punishment attached to a murder

conviction and the moral blameworthiness of the offender. Accordingly, it is a

principle of fundamental justice that a conviction for murder cannot rest on

anything less than proof beyond a reasonable doubt of subjective foresight of

death. Since s. 213 of the Code expressly eliminates the requirement for

proof of subjective foresight, it infringes ss. 7 and 11(d) of the Charter: R.

v. Martineau, [1990] 2 S.C.R. 633.

This Court’s

decision in Vaillancourt, supra, cannot be construed as saying that, as

a general proposition, Parliament cannot ever enact provisions requiring

different levels of guilt for principal offenders and parties. It must be

remembered that within many offences there are varying degrees of guilt and it

remains the function of the sentencing process to adjust the punishment for

each individual offender accordingly. The argument that the principles of

fundamental justice prohibit the conviction of a party to an offence on the

basis of a lesser degree of mens rea than that required to convict the

principle could only be supported, if at all, in a situation where the sentence

for a particular offence is fixed. However, currently in Canada, the sentencing

scheme is flexible enough to accommodate the varying degrees of culpability

resulting from the operation of ss. 21 and 22 of the Criminal Code. That

said, however, there are a few offences with respect to which the operation of

the objective component of s. 21(2) will restrict the rights of an accused

under s. 7. If an offence is one of the few for which s. 7 requires a minimum

degree of mens rea, the decision in Vaillancourt does preclude

Parliament from providing for the conviction of a party to that offence on the

basis of a degree of mens rea below the constitutionally required

minimum. Therefore, the question whether a party to an offence had the

requisite mens rea to found a conviction pursuant to s. 21(2) must be

answered in two steps. Firstly, is there a minimum degree of mens rea

which is required as a principle of fundamental justice before one can be

convicted as a principle for this particular offence? If there is no such

constitutional requirement for the offence, the objective component of s. 21(2)

can operate without restricting the constitutional rights of the party to the

offence. Secondly, if the principles of fundamental justice do require a

certain minimum degree of mens rea in order to convict for this offence,

then that minimum degree of mens rea is constitutionally required to

convict a party to that offence as well. As stated in Vaillancourt, the

principles of fundamental justice require a minimum degree of mens rea

for only a very few offences. The criteria by which these offences can be