Judicial Control of Querulous Litigants by Mr. Justice Yves-Marie Morissette, Quebec Court of Appeal (2008)

DOSSIER: EXTREME BEHAVIOR

|

1. |

Extreme Behavior |

2. |

Extreme Behavior – “Querulousness” by Dr. Jacques Gagnon |

3. |

Extreme Behavior – “Judicial Control of Querulous Litigants” by Mr. Justice [sic] Yves-Marie Morissette |

4. |

Extreme Behavior – “A Portrait of Querulous Behavior” by Le Spécialiste “with the kind collaboration of Mr. Justice Y.-M. Morissette” |

| 5. |

Elsevier – “Evaluation de la dangerosité du malade mental psychotique” / “Dangerousness evaluation of psychotic patient” by F. Millaud and J.-L. Dubreucq, Psychiatrists. (Available online in 2005) [This is a French article with a bilingual abstract. Judicial Madness has provided an exclusive English translation of the article.] |

3.

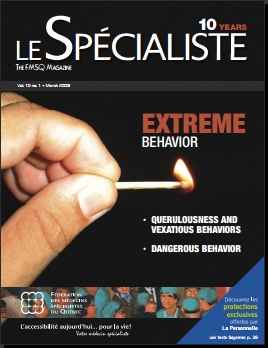

Le Spécialiste, The FMSQ Magazine Vol. 10 no. 1 – March 2008, EXTREME BEHAVIOR, Querulousness and Vexatious Behaviors, Dangerous Behavior (Cover)

EXTREME BEHAVIOR

Judicial Control of Querulous Litigants by Mr. Justice Yves-Marie Morissette, Quebec Court of Appeal (2008)

Source: Le Spécialiste, The FMSQ Magazine Vol. 10 no. 1 – March 2008, EXTREME BEHAVIOR, Querulousness and Vexatious Behaviors, Dangerous Behavior (Cover). Download the English edition of the magazine here: Vol 10 no 1 Le Spécialiste, The FMSQ Magazine Vol. 10 no. 1 – March 2008. Special issue featuring a “Dossier” on EXTREME BEHAVIOR

Download the French edition of the same magazine here:

Judicial Control of Querulous Litigants

A “querulous person” is defined in the Rules of the Code of Civil Procedures [sic] as someone who, while exercising his/her right to start legal proceedings, will do it in an excessive or unreasonable manner. A further definition in the Grand Robert de la langue française also gives an accurate idea of the troubling behavior observed in certain litigants:

“A pathological tendency to seek out quarrels and to claim compensation for a prejudice, real or imaginary, in a manner disproportionate to the case”.

Although there are few vexatious or querulous litigants in absolute numbers, such individuals create serious problems for the people who have to face them in court and they take up the time and resources of the courts to an egregious degree. One characteristic of such people is that they represent themselves, either because they do not want to retain legal counsel or because they cannot find a lawyer prepared to represent them.

Judicial control of the problem

Since 2003, various regulatory provisions have been adopted in Quebec to permit certain courts to control the behavior of litigants with this type of profile. Local jurisprudence had, in fact, already introduced such measures several years beforehand. A 1994 case, Yorke vs. Paskell-Mede [Yorke], which set a precedent, established that, in exercising its “inherent” powers, the Superior Court can, by special order, prevent the abuse of process by vexatious litigants.

Since 2003, various regulatory provisions have been adopted in Quebec to permit certain courts to control the behavior of litigants with this type of profile. Local jurisprudence had, in fact, already introduced such measures several years beforehand. A 1994 case, Yorke vs. Paskell-Mede [Yorke], which set a precedent, established that, in exercising its “inherent” powers, the Superior Court can, by special order, prevent the abuse of process by vexatious litigants.

It might therefore be thought that the legal system’s apprehension concerning this phenomenon is fairly recent, and that everything necessary has already been done to contain the most obvious occurrences. The reality, however, is not so simple.

The origin of control measures

First of all, it is very likely that this phenomenon, even though it may be marginal statistically speaking, has existed here for a very long time. It was in 1887 that the British courts made official the type of judicial control that became part of Quebec jurisprudence in 1994. A well-known vexatious litigant, Hector William Grepe, plagued the courts in a civil suit that lasted several years and on which final judgment was rendered in 1879. On several occasions after that date, Grepe again tried to apply to the court to reopen the same dispute. Finally, in November 1887, the English Court of Appeal, in its decision on Grepe v. Loam [Grepe] required that henceforth he first obtain the court’s leave before initialing any further proceedings relating to the same affair. The court referred to a previous, unreported decision in Suir v. Newton (date unknown), where it had issued the same type of order.

Several years later, in 1896, the British Parliament, concerned by the problem of vexatious litigants (of whom querulous litigants are probably the most harmful) adopted a law that generalized the mechanism created by the Grepe decision, with a few changes. Under this law, the Attorney General could henceforth apply to the High Court for an order prohibiting a vexatious litigant from taking any type of legal action without first obtaining the permission of a judge of that same court. The party being harassed by a vexatious litigant could always apply for a Grepe order. In addition, the Attorney General could intervene to prevent vexatious litigants from multiplying abusive proceedings against new parties.

The solution under Quebec law

Aside from a few nuances, the measures now in place in Quebec seek the same objectives as those adopted more than a century ago in England. Firstly, the Yorke system of orders is very like that of Grepe orders. Secondly, even though Quebec law has no text similar to the 1896 British Act, the higher courts have adopted internal management rules that give virtually the same result. These are articles 84 to 90 of the Rules of Civil Proceedings [sic] of the Superior Court of Quebec and articles 94 and 95 of the Rules of the Quebec Court of Appeal in Civil Matters. [Emphasis added JMad.]

In extreme cases, under articles 85 (Superior Court) and 95(2) (Court of Appeal), the court can even bar physical access to its premises. This measure, which is meant to protect court employees in particular, may seem draconian in nature, but that denotes an incomplete understanding of the problem. The Quebec courts, once again, no doubt based their decision on a British precedent. In 2002, in Attorney General v. Ebert, the Appeal Court in England handed down an important decision imposing this type of prohibition against a vexatious litigant called Ebert. The facts of the matter illustrate the often dramatic nature of such a litigant’s behavior. Despite four Grepe orders being issued against him and a further order obtained by the Attorney General under the Act already mentioned above, Ebert, according to the evidence, persisted and, among other actions, had, in the course of about three and a half years made at least 151 applications for permission to issue fresh proceedings. Along the way, he behaved in a thoroughly outrageous manner towards court employees. Several years before the Ebert order in 2002, the Quebec Court of Appeal in a virtually unnoticed decision in 1996 had confirmed a similar measure that barred a citizen “from communicating by fax or telephone, directly or via a third party, with any judge of the Superior Court of the Quebec City Appeal District or with any secretary or other employee in the support personnel of the judges of the Superior Court, at any fax or telephone number in service at the Palais de justice in Quebec City”.

Another tool that can be used by parties targeted by vexatious litigants was also introduced when these regulatory measures were adopted. Article 90 of the Superior Court Rules of Civil Procedure provides that, when an order is issued, “the clerk shall forward a copy of such order filed in his court to clerks of the court in all judicial districts and to the Chief Justice in Montreal for inclusion in the public register covering vexatious litigation”.

The intranet site of the Ministère de la Justice keeps an up-to-date list of all inclusions in the register; this means that it can also be used to consult judgments applying the Yorke precedent or the provisions of the Rules of Civil Procedure concerning vexatious litigants. As at December 31, 2007 ninety-five persons or entities were shown on the register: 67 men, 26 women and two groups of persons. Some of these litigants were covered by a number of orders - as many as five in one instance, and sometimes two or three, showing that the person in question had taken action against several successive parties. There is every reason to think, however, that this list only provides an incomplete picture of the reality. It is common for judges to see parties appear in their court who have no legal counsel and who fit the profile of a vexatious litigant, without however having been declared as such by court order. Traces of such behavior can be found in published jurisprudence, both before and after 1994, without the authors of the abusive proceedings having been the subject of an order requiring that they receive permission before they could access the justice system.

These measures are supplemented by the means available to litigants under common law to terminate an abusive dispute or to remedy its prejudicial effects. This is the case in the peremptory dismissal, in response to an application made under article 75.1 of the Code of Civil Proceedings [sic], of procedures that are clearly frivolous or unfounded; the peremptory dismissal under article 501 of the same Code of abusive, time-consuming appeals or those that have no reasonable chance of success; as well as amounts awarded to the party who is a victim of an abusive procedure, and damages obtained by taking legal action against the party abusing its right to access justice.

Finally, during the exercise of their inherent or general powers, courts of common law can control the procedures taking place before them and thus neutralize some of the abusive behavior typical of vexatious litigants.

The effectiveness of control measures

Positive law in Quebec has developed greatly since the mid-1990′s. There is therefore no doubt that people confronted with a vexatious litigant and forced to defend themselves now have greater resources at their disposal than they did ten to fifteen years ago. Nonetheless, they still have to be patient and suffer several assaults before being able to benefit from the control measures introduced in 2003. In the meantime, problems and often major costs accrue, and these are beyond the intervention of the courts, even today.

Just recently, the Superior Court handed down a decision on an action by Valery I. Fabrikant, the same person that the court declared vexatious in 2000. The case had started in 1995 (therefore, prior to the restrictions being imposed) and had been going through the courts since that time. In the decision dismissing this action, the judged charged with the matter noted that:

[30] [Fabrikant] acts like someone who, having nothing else to do, enjoys taking unfounded legal action. He obviously does not care what consequences this has for others; in fact, the opposite is true. His provocative attitude, his sniggering and his insults show that he is acting deliberately and maliciously, and he clearly enjoys it

(31] We forget too often that defendants also have rights, that they are citizens who can go before the courts and that they are entitled to the protection of the Law and the legal system. The courts cannot leave them at the mercy of vexatious litigants who, in some cases, become veritable torturers. We are however forced to admit that that is what is happening here, in direct contravention of article 7 of the Civil Code of Quebec already cited.

[32] We have seen above that this case, begun more than 15 years ago, has absolutely no chance of succeeding. It has, however, haunted the defendants throughout that time. It has not allowed them to forget the killings committed by Fabrikant on August 24,1992 at Concordia University where they were professors. The emotion and distress of Doctors Sankar and Swamy throughout their examination by the defendant was obvious. The pleasure Fabrikant took in seeing them suffer was equally obvious.

Awarding damages for abuse of the right to access justice can sometimes partially remedy problems of this nature. But the question is whether the party against whom the award is made – the party whose vexatious behavior risks appearing either as a defendant or a claimant – is able to fulfill the judgment made. In a case like this, it would be most unlikely.

In addition, while some courts have specific judicial means to prevent the most prejudicial effects of vexatious actions, the same is not true of administrative tribunals, which cannot rely on the “inherent” powers referred to at the beginning of this text. Yet a very high proportion of Quebec litigation is, first, the responsibility of such bodies. Some, like the Commission des lesions professionnelles, have the legal right to subject abusive recourse to certain conditions. But we are still far from control orders which do not target the recourse taken, but the actual vexatious litigant.

The undoubtedly relative effectiveness of the control measures described here call for deeper reflection on the fundamental causes of the problem that they are designed to relieve or even eliminate.

The immediate reason for the problem is a personality disorder which, in its extreme form, can be transformed into paranoia. Vexatious behavior falls, first and foremost, within the field of psychiatry and it is up to specialists in this discipline to determine the appropriate treatment.

But extraneous factors may very likely exacerbate the behavior of vexatious litigants. As long as such factors remain, vexatious actions will continue at the edge of the judicial system. Two theories deserve particular mention in this respect.

The first is that of anomie, a sociological concept first described by Emile Durkheim and explored in his La Division du travail social (1893) and Le Suicide (1897). It can be defined as the temporary lack of regulatory social norms that ensure cooperation between specialized functions, or as a sickness resulting from uncontrolled human desire, a lack of definite goals and uncertainty about legitimate hopes. In a thesis published in 1999, one author explained Valery Fabrikant’s behavior as being the consequence of institutional anomie at Concordia University: in short, since he had never encountered real resistance, he was carried away by his tendencies and then his mania until, finally, he became dangerous.

The second theory presents certain similarities with the first. It suggests that the growing incidence of vexatious litigants before the courts and administrative tribunals is perhaps an unfortunate effect of the desire demonstrated to facilitate access to justice. An international symposium was held in June 2006 at Prato, near Florence, on access to justice and vexatious or querulous litigants. In a speech upon this occasion, Sir Anthony Clarke, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice in England, stated that a total of 175 orders were issued up until 2006 under the Vexatious Actions Act of 1896. Eighty-eight of these arose after 1995, the year in which a major reform to simplify civil procedure and reduce its costs came into effect. Judge Clarke found that there was a relationship of cause and effect between these two phenomena:

Simplifying procedure brings with it the obvious benefits of cost and time-savings for litigants and the courts - benefits which all civil justice systems continue to spend considerable time and effort in seeking to achieve. It also has the benefit that it opens up access to the courts to those who cannot afford legal representation, or for perfectly valid reasons choose not to appoint such representatives. Those are the benefits. Unfortunately it also creates the circumstances where, with greater ease than under a more complicated regime that required the input of legal professionals before a claim could be commenced, a litigant in person (LIP) can more easily bring vexatious claims. The greater ability to bring claims gives rise to a greater ability to bring vexatious claims.

The same idea has already been put forward with regard to Quebec law, where a reform of civil procedure comparable in scope to the British reform, came into effect in 2002.

Other factors undoubtedly tend to exacerbate the problem, one example most certainly being the increasing cost of legal services which drives people going before the courts to act on their own behalf. It would be futile to believe that the solution to the problem is exclusively clinical in nature

Notes

1 [1996] R.J.Q. 1964 (C.A.). |

2 (1887) 37 Ch.D. 168 (CA). |

3 An Act to prevent Abuse of the Process of the High Court or other Courts by the Institution of Vexatious Proceedings, 1896 (the « Vexatious Actions Act »). |

4 [2002] 2 All E.R. 789 (C.A.). |

5 Droit de la famille – 2500, J.E. 96-1846 (C.A.) |

6 See Saraffian c. SMBD — Jewish General Hospital, J.E. 2005-24 (C.A.) et Wozny c. R, J.E. 2005-802 (C.A.). |

7 2007 QCCS 5431. |

8 See the Loi sur les accidents du travail et les maladies professionnelles, L.R.Q., c. A-3.001, art. 429.27, and the Loi sur la justice administrative, LR.Q., c. J-3, art. 115. See, the Charte des droits et libertés de la personne, L.R.Q., c. C-12, art 77, al. 2,1 °, the Code du travail, L.R.Q., c. c-27, art. 188,1°, the Loi sur la police, LR.Q., c. P-13.1, art. 168,1 ° and article 143.1 of the Code des professions, L.R.Q., c. C-26, in effect December 18, 2007 through the Loi modifiant la Loi sur le Barreau and the Code des professions, LQ. 2007, c. 35. |

9 Boudon, Raymond et François Bourricaud, Dictionnaire critique de la sociologie (2e ed.), Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 2002. |

10 Beauregard, Mathieu, La folie de Fabrikant, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1999. |

11 Morissette, Yves-Marie, « Abus de droit, quérulence et parties non représentées » (2003), 49 Revue de droit de McGill 23, p. 34-8. |