Pathology and Therapeutic of the

Warlike Litigant

Foreword

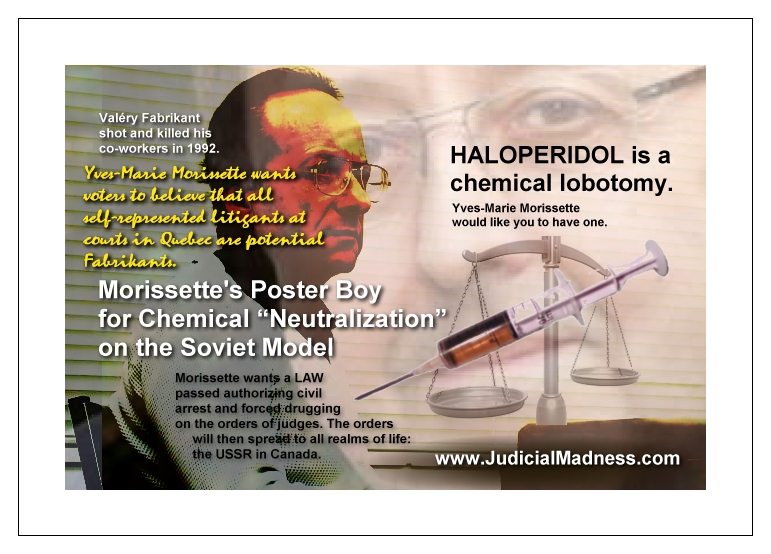

This featured item is an exclusive English translation of an article in French by Yves-Marie Morrissette, Rhodes Scholar and legal adviser to the veiled Communist Parti Québécois (PQ). (You can read the PQ’s Communist manifesto of 1972 or download it from the sidebar at CANADA How The Communists Took Control.)

The French article translated here, Pathologie et thérapeutique du plaideur trop belliqueux, first appeared in 2001 in volume 155 of a yearly journal of the Quebec Bar Association. The title of the journal in French is Développements récents en déontologie, droit professionnel et disciplinaire. My translation: Recent Developments in Ethics, Professional Law and Discipline. The journal is published for the Quebec Bar Association’s permanent training service by Les Editions Yvon Blais Inc, ISBN 2-89451-497-2.

Pathologie was published again in 2002 under a new citation: (2002) 33 R.D.U.S. 251, in the Revue de droit de l’Université de Sherbrooke.

Its importance lies in the facts (i) that it has been used to professionally train lawyers and judges, (ii) although its author is a lawyer, not a psychiatrist, and has no formal qualifications in psychiatry. Nevertheless, in this article, lawyer Morissette purports to “diagnose” a new mental illness, which he attributes to a class of people, pro-se litigants; a class which could obviously be expanded at any time to include other groups of people in other situations. Having “diagnosed” his target class, Morissette has the “treatment” ready in the form of state guardianship, and forced drugging with the Soviet drug of choice, haloperidol (see p. 171, below), a neuroleptic known to cause brain damage.

As former Soviet dissident Alexander Podrabinek said in “An Address to the Psychiatric Community” aired on October 14, 1988 at a symposium of the International Association on the Political Use of Psychiatry held in Washington, DC, and translated by Andrew Meier:

“In the last two years there’s been a sharp decrease in the number of judicial trials that have led to the committal to “ordinary” or “special” (i.e. high-security) psychiatric hospitals of healthy, or perhaps unhealthy, citizens, on political grounds. That there are fewer trials no one, I think, will dispute. But at the same time, there are still many people in the ordinary psychiatric hospitals.”

Moreover, on reading his articles and interviews, it is clear that Morissette knows what he is doing. He is introducing the Soviet system of political control to Quebec. (See selected quotations.)

Pathologie et thérapeutique du plaideur

trop belliqueux

Pathology and Therapeutic of the

Warlike Litigant

169

|

Survol du sujet |

Overview of the Subject |

|

Le texte qui suit porte sur certaines des formes que revêt la procédure abusive dans le cadre de litiges civils. L’expression «procédure abusive» évoque d’emblée une forme de l’abus de droit1, et donc un comportement fautif susceptible d’entraîner la responsabilité de son auteur. Mais ce n’est là qu’un aspect parmi plusieurs autres de la procédure abusive. Celle-ci, en effet, traduit une réalité composite, qui se déploie de nos jours sur bien d’autres plans que celui, classique, de la responsabilité civile. Tout le monde s’entend, il semble bien, pour qualifier cette réalité de fâcheuse et souhaiter qu’on en supprime ou qu’on en contienne les manifestations. Je voudrais pour ma part dresser ici un inventaire sommaire de certaines difficultés analytiques que présente cette réalité, et passer en revue divers moyens dont le droit dispose pour y remédier2. L’inventaire livré ici n’a aucune prétention à l’exhaustivité. Il vise essentiellement à ouvrir le champ du débat et à faire ressortir certains aspects moins connus du sujet en question. Outre le problème encore une fois classique de la responsabilité civile pour recours abusif, l’abus de procédure donne ouverture à des condamnations spéciales aux dépens, des injonctions interdisant selon diverses modalités le recours aux tribunaux ou à d’autres instances, des ordonnances judiciaires comportant une interdiction du même genre au motif qu’un plaideur est «vexatoire», des mesures de redressement — dont le rejet de la procédure abusive — conformes aux articles 75.1, 75.2 et 524 C.p.c. et des recours disciplinaires contre les |

The text which follows bears on certain of the forms under which the abusive procedure is manifested in the framework of civil litigation. The expression “abusive procedure” evokes from the outset a form of “abuse of right”1, and thus, offending behavior susceptible of entailing the liability of its author. But this is only one aspect of the abusive procedure, among many others, which translates a composite reality that nowadays manifests in many other ways than the classic one of civil liability. Everyone will surely agree, for example, that this is a troublesome reality and desire that its manifestations be done away with, or contained. I would like to draw up a short list of certain analytical difficulties that this reality presents, and review the various remedial measures at the disposal of the law.2 The list makes no claim to being exhaustive. It essentially aims to initiate a debate and to highlight certain lesser known aspects of the question. Aside from the once again classic problem of civil liability for abusive recourse, abuse of procedure raises the prospect of the special imposition of costs, of injunctions according to various modalities prohibiting access to the courts or to other instances, judicial injunctions including a prohibition of the same kind on the grounds that the pleader is “vexatious”, corrective measures including the setting aside of the abusive procedure in accordance with sections 75.1,75.2 and 524 C.C.P. and disciplinary measures against the |

|

1. Il s’agit, spécifiquement, du droit d’ester (ou d’agir) en justice.

|

1. Specifically, the right to exercise legal procedures.

|

|

170 Développements Récents En Déontologie |

170 Recent Developments in Professional Ethics |

|

avocats. Il n’est pas question de traiter ici de tous ces sujets. Je veux m’arrêter sur deux aspects de la procédure abusive: ses principales causes (I- Eléments de diagnostic) et quelques-uns des moyens qui ont actuellement la faveur des tribunaux pour remédier à ces abus (II- Principaux remèdes). |

lawyers. There is no question of dealing here with all these subjects. I want to focus on two aspects of the abusive procedure: its principal causes (I- Diagnostic Elements) and a few of the measures currently favored by the courts to remedy these abuses (II- Main remedies). |

|

I- Éléments de Diagnostic |

I- Diagnostic Elements |

|

1. Aspects subjectifs: la quérulence, une pathologie du sujet de droit |

1. Subjective aspects: Querulousness, a pathology of the subject of the law |

|

Derrière tout abus de procédure, et de manière plus générale derrière toute initiative judiciaire hasardeuse, se trouve un sujet de droit qui, en demande ou en défense, prétend exercer un droit quelconque, susbstantive or procedural selon une distinction commode plus facile à exprimer en anglais qu’en français. Mettons de côté pour le moment les situations où le mandataire ad litem, habituellement pour cause d’incompétence ou de vénalité, est l’instigateur de l’abus. A-t-on identifié une attitude, une pathologie même, qui soit caractéristique du sujet de droit incapable de la moindre concession lorsque ses droits lui paraissent mis en cause? Oui, on l’a fait. Cette pathologie ou ce déséquilibre se nomme la quérulence. Elle est définie comme suit dans deux dictionnaires usuels: (i) Tendance morbide à rechercher les querelles et à revendiquer des droits imaginaires, caractéristique de certaines psychoses, (ii) Tendance pathologique à se plaindre d’injustices dont on se croit victime3. La quérulence a été étudiée sous divers angles. À défaut d’une étiologie précise, il en existe une symptomatologie assez détaillée4. Elle survient surtout |

Behind every abuse of procedure, and more generally behind every risky legal initiative, there is a subject of the law who, in demand or in defense, claims to exercise some right, substantive or procedural according to a useful distinction more easily expressed in English than in French. Put aside for the moment those situations where the attorney ad litem, usually on account of incompetence or venality, is the instigator of the abuse. Have we identified an attitude, a pathology even, which is characteristic of the subject of the law who seems incapable of the least concession when, in his view, his rights are at issue? Yes, we have. This pathology or this imbalance is called querulousness. It is defined as follows in two conventional dictionaries: (i) A morbid tendency to quarrel and to lay claim to imaginary rights, characteristic of certain psychoses, (ii) A pathological tendency to complain of injustices of which one believes one is the victim. Querulousness has been studied from various angles. In the absence of a precise aetiology, there is a quite detailed symptomatic4. It emerges especially |

|

3. Ces définitions sont tirées, respectivement, du Petit Robert et du Dictionnaire Hachette de la langue française. Rowlands, dans l’article cité infra (1988), a proposé la définition suivante, reprise plus tard par Ungvari et al., infra (1997); “[...] an overvalued idea of having been wronged, that dominates the mental life, and results in behaviour directed to the attainment of justice, and which causes significant problems in the individual’s social and personal life. It usually, but not always, involves petitioning in the courts or other agencies of administration.”

|

3. These definitions are drawn, respectively, from the Petit Robert and from the Dictionnaire Hachette de la langue française [Hachette's Dictionary of the French language]. Rowlands, in the article cited infra (1988), proposed the following definition, later taken up by Ungvari & al., infra (1997): “[...] an overvalued idea of having been wronged, that dominates the mental life, and results in behavior directed to the attainment of justice, and which causes significant problems in the individual’s social and personal life. It usually, but not always, involves petitioning in the courts or other agencies of administration.”

|

|

Pathologie et Thérapeutique du Plaideur 171 |

Pathology and Therapeutic of the Litigant 171 |

|

entre 40 et 60 ans; elle se caractérise par une lucidité apparente, «logical, albeit fundamentally flawed, reasoning and a usually formal manner»5. Un signe qui, en général, ne trompe pas, est que le plaideur quérulent se représente lui-même. Dans sa forme la plus virulente, la quérulence comporte un délire de persécution qui relève de la paranoïa, avec laquelle elle finit par se confondre; mais elle peut varier en intensité et tous les sujets ne sont pas également délirants. On a même avancé un traitement pour cette affection, à base de médicaments comme l’haloperidol et le pimozide6. |

between 40 and 60 years of age; it is characterized by an apparent lucidity, “logical, albeit fundamentally flawed, reasoning and a usually formal manner”5. One sign which, in general, is unmistakable, is that the querulous litigant represents himself. In its most virulent form, the querulousness includes a persecution delirium arising from the paranoia, with which it is confused in the end; but it can vary in intensity and not all subjects are equally delirious. A treatment has even been advanced for this affliction, based on medications such as haloperidol and pimozide6. |

|

Il n’est évidemment pas question de prétendre ici que l’abus de procédure n’est qu’un problème psychiatrique. Bien sûr que non. Mais il est utile de savoir que le problème juridique peut avoir une origine psychiatrique, que certaines personnes pathologiquement incapables de porter un regard critique sur leur propre situation trouvent dans la multiplication de revendications et de recours de toutes sortes une exutoire à leur insatiable sentiment d’injustice. Certaines espèces locales semblent bien illustrer la chose. |

Obviously, there is no question here of saying that the abuse of procedure is only a psychiatric problem. Certainly not. But it is useful to know that the legal problem can have a psychiatric origin, that certain people pathologically incapable of self-criticism of their own situation, find in the multiplication of claims and recourses of all sorts an executor for their insatiable sentiment of injustice. Some local specimens seem to illustrate this very well. |

|

Ainsi, on ignore quelle est la teneur précise du diagnostic psychiatrique qui aura été porté sur la personne de Valéry Fabrikant avant son procès aux assises criminelles7 mais son comportement pendant ce procès et certaines des initiatives qu’il prit postérieurement à sa condamnation semblaient bien dénoter un cas patent de quérulence. Le nombre de poursuites et de recours de toutes sortes intentés par lui8, le caractère tout à fait inusité mais inventif de cer- |

So, we are unaware of the specific tenor of the psychiatric diagnosis that would have been made of Valéry Fabrikant before his criminal trial 7, but his comportment during the trial and certain of the initiatives that he took after his sentencing seemed surely to denote a patent case of querulousness. The number of pursuits, and of recourses of all kinds instituted by him8, the quite novel but inventive character of cer- |

|

R.D. Maier, G.J. Blancke et F.W. Doren, «Litigiousness as a Resistance to Therapy», (1986) 14 Journal of Psychiatry & Law 109; C. Astrup, «Querulent Paranoia: A Follow-Up», (1984) 11 Neuropsychobiology 149; Ralph Bolton, «Differential Aggressiveness and Litigiousness: Social Support and Social Status Hypotheses», (1979) 5 Aggressive Behaviour 233; il existe aussi en langue allemande un traité sur le même sujet, mais il est déjà ancien: Karl L. Kruska, Ein Beitrag zur Lehre vont Querulantenwahn, Berlin, E. Ebering, 1897.

|

R.D. Maier, G.J. Blancke and F.W. Doren, «Litigiousness as a Resistance to Therapy», (1986) 14 Journal of Psychiatry & Law 109; C. Astrup, «Querulent Paranoia: A Follow-Up», (1984) 11 Neuropsychobiology 149; Ralph Bolton, «Differential Aggressiveness and Litigiousness: Social Support and Social Status Hypotheses», (1979) 5 Aggressive Behaviour 233; there is also a German-language treatise on the same subject, but it it is old now: Karl L. Kruska, Ein Beitrag zur Lehre vont Querulantenwahn, Berlin, E. Ebering, 1897.

|

|

172 Développements Récents En Déontologie |

172 Recent Developments in Professional Ethics |

|

tains arguments qu’il faisait valoir9, l’extrême ténacité dont il faisait montre10, ainsi que les manifestations anciennes chez lui de cette prédisposition11, paraissaient tous symptomatiques. Ces comportements, loin de soulever un doute sur l’acuité intellectuelle de l’intéressé, tenderaient au contraire à démontrer qu’il jouissait d’une intelligence supérieure à la moyenne. La quérulence, en effet, est un problème d’affect et non d’intellect. Même s’il existe des cas comparables à celui que je viens d’évoquer12, il est raisonnable de supposer, comme je le disais plus haut, |

tain arguments that he advanced9, the extreme tenacity that he showed10, as well as the older manifestations in him of this predisposition11, all seemed symptomatic. These behaviours, far from raising a doubt as to the intellectual acuity of the person concerned, would tend on the contrary to demonstrate that he enjoyed above-average intelligence. Querulousness, in effect, is a problem of affect and not of intellect. Even if cases12 comparable to this exist, it is reasonable to suppose, as I said above, |

|

même demandeur. Ces initiatives, et quantité d’autres, ont rencontré un obstacle dans Fabrikant c. Corbin, JE. 2000-1347 (CS).

|

same litigant. These initiatives, and a quantity of others, encountered an obstacle in Fabrikant v. Corbin, JE. 2000-1347 (CS).

|

|

Pathologie et Thérapeutique du Plaideur 173 |

Pathology and Therapeutic of the Litigant 173 |

|

que la quérulence peut varier en intensité d’un sujet à l’autre, et que certaines personnes peuvent n’en être atteintes que de façon intermittente. Ce désordre psychologique sérieux me parait donc indissociable de toute analyse approfondie du sujet abordé ici; il est l’un des éléments pathogènes de l’abus de procédure et mériteraït à ce titre qu’on s’y intéresse plus à fond. |

that querulousness may vary in intensity from one subject to another, and that some people may be affected only intermittently. This serious psychological disorder thus appears to me indissociable from any analytical probe of the subject broached here; it is one of the disease elements of the abuse of procedure and as such would merit deeper investigation. |

|

2. Aspects déontologiques et disciplinaires: les comportements fautifs des auxiliaires de la justice |

2. Professional ethical and disciplinary aspects: offending behaviours of the auxiliaries of Justice |

|

Entre le sujet de droit, dont nous venons de parler, et l’institution à laquelle il s’adresse, dont il sera question plus loin, intervient habituellement un avocat ou une avocate. L’avocat, en tant qu’auxiliaire de la justice, n’est pas toujours à la hauteur des attentes qu’une partie peut légitimement entretenir à son endroit. Les “circonstances”13, les retards injustifiés14, l’incompétence15 ou une mauvaise foi apparente16, font partie de l’éventail des causes qui ralentissent et compliquent inutilement les dossiers litigieux. Il en a probablement toujours été ainsi. Dans certains cas aussi, ce qui est plus grave, la malhonnêteté17, voire la crapulerie pure et simple18 (certains mots ne sont pas trop forts), faussent le rapport de droiture ou de rectitude qui |

Between the subject of the law, of which we have just spoken, and the institution he addresses, to be discussed later, a lawyer typically intervenes. The lawyer, as the auxiliary of justice, is not always up to the expectations that a party can legitimately entertain of him. The “circumstances”13, the unjustified delays14, the incompetence15 or the apparent bad faith16, are part of the variety of causes which slow down and uselessly complicate court files. It has probably always been this way. In certain cases as well, which is more serious, the dishonesty17, frankly the pure and simple fraudulence 18 (some words are not too strong), falsifies the relationship of uprightness or of rectitude which |

|

compte tenu du nombre et la diversité des contestations élevées par les intéressés, que les affaires York c. Paskell-Mede, infra, note 51 et Byer, infra, note 57.

|

given the number and diversity of the challenges raised by the persons concerned in the matters of York c. Paskell-Mede, infra, note 51 and Byer, infra, note 57.

|

|

174 Développements Récents En Déontologie |

174 Recent Developments in Professional Ethics |

|

doit exister entre l’institution et l’avocat. Il arrive aussi que l’avocat lui-même donne des signes de quérulence (quoique, dieu merci, cela soit rare19) ou que, se représentant lui-même, il fasse montre, malgré des états de service enviables dans sa profession, d’une opiniâtreté condamnable20. En réalité, aux mains de l’avocat, le recours abusif change habituellement de mobile. Ce n’est plus la conviction d’avoir raison, mais la volonté implacable de gagner, qui explique les choses, et on connaît des espèces où le client est en quelque sorte impuissant devant l’excessive bellicosité, sinon la rapacité, de son avocat. Il ne s’agit plus de quérulence. Tout ici est empreint de lucidité, d’une pugnacité farouche qui conduit l’avocat à instrumentaliser l’institution juridique (en général, le tribunal, la procédure contentieuse, etc.) pour |

must exist between the institution and the lawyer. It also happens that the lawyer himself shows the signs of querulousness (albeit, thank god, rarely19) or that, when representing himself, he exhibits a condemnable obstinacy, despite an enviable history of service in his profession20. In reality, in the hands of the lawyer, the abusive procedure habitually changes in quality. It is no longer the conviction of being right, but the implacable will to win, which explains things, and situations are known where the client is, as it were, powerless before the excessive bellicosity, if not the rapacity, of his lawyer. It is no longer querulousness. Here, all is characterized by lucidity, by a fierce pugnacity which leads the lawyer to use the legal institution (in general, the tribunal, adversarial procedure, etc.) as a tool to |

|

19. Je concède tout de suite qu’il en existe peu d’exemples. Re Duncan, (1958) R.C.S. 41, me paraît être une espèce de ce genre, d’ailleurs assez triste. En 1972, alors que j’étais encore étudiant en droit, j’ai travaillé pendant quelques mois pour un avocat, membre du Barreau de l’Ontario et conseiller d’une société de la Couronne, qui avait connu Duncan. Il me raconta à l’époque que, quelque temps après l’incident d’audience relaté dans ce jugement, Duncan fut interné dans un hôpital psychiatrique. Je n’ai pu vérifier si ces détails sont exacts. Nul doute que la quérulence soit un grave handicap pour un plaideur de métier. L’incident qui en 1995, au cours d’une plaidoirie devant la Cour suprême du Canada, mit en scène l’avocat Bruce Clark, présente peut-être des points de ressemblance avec Re Duncan (voir Jim Bronskill, “High court chastises lawyer seeking aboriginal review,” dépêche de la Presse Canadienne du 12 septembre 1995: “[...] Clark contends the judiciary has long engaged in treasonable, fraudulent and genocidal practices by ignoring native sovereignty over tracts of land [...]. “In my 26 years as a judge, l’ve never heard anything so preposterous,” Lamer told Clark during a one-hour hearing punctuated by heated exchanges. “I don’t accept that and I think you’re a disgrace to the bar.” [...] Clark said he would appeal the high court decisions to the judicial committee of the British Privy Council. [...] The Law Society of Upper Canada is one step away from disbarring Clark for prevîous incidents, including calling a judge racist.”). Mais, dans ce cas-ci, l’avocat avait pris fait et cause pour son client au point, semble-t-il, de sacrifier toute objectivité dans l’appréciation de la situation (je suppose, d’ailleurs, qu’à ses propres yeux il n’était pas personnellement en cause). Il va de soi que des espèces comme Descôteaux, infra, note 31, ou Belhassen, supra, note 17, présentent un tableau tout à fait différent, marqué par une évidente malhonnêteté. Plus banale, mais néanmoins préoccupante, est une espèce comme Marchand (Litigation guardian of) c. Public General Hospital of Chatham (2000), 51 O.R. (3d) 97 (C.A.), où il n’y a ni quérulence ni malhonnêteté, mais une hostilité persistante et réciproque entre les avocats, censurée par la Cour d’appel de l’Ontario en ces termes (§§ 5 et 169): “The trial was characterized by an extraordinary level of rancour and hostility on the part of counsel, all of whom were, regrettably, senior members of the bar of Ontario. It was not a trial of which the administration of justice can be proud. [...] The trial judge cannot be criticized, let alone be found guilty of judicial bias, for his occasional mild rebuke to counsel.”

|

19. I immediately concede that there are few examples. Re Duncan, (1958) R.C.S. 41, appears to me to be a case of this type, and quite sad. In 1972, when I was still a law student, I worked for a lawyer for a few months who was a member of the Bar of Ontario and counsel to a Crown corporation, who had known Duncan. At that time, he told me that shortly after the hearing incident related in this judgment, Duncan was interned in a psychiatric hospital. I have not been able to verify whether these details are accurate. No doubt querulousness is a serious handicap for a professional barrister. The incident which in 1995, in the course of a plea before the Supreme Court of Canada, placed lawyer Bruce Clark in the spotlight, may present points of similarity with Re Duncan (see Jim Bronskill, “High court chastises lawyer seeking aboriginal review,” Canadian Press press release of September 12th, 1995: “[...] Clark contends the judiciary has long engaged in treasonable, fraudulent and genocidal practices by ignoring native sovereignty over tracts of land [...]. “In my 26 years as a judge, l’ve never heard anything so preposterous,” Lamer told Clark during a one-hour hearing punctuated by heated exchanges. “I don’t accept that and I think you’re a disgrace to the bar.” [...] Clark said he would appeal the high court decisions to the judicial committee of the British Privy Council. [...] The Law Society of Upper Canada is one step away from disbarring Clark for previous incidents, including calling a judge racist.”). But, in this case, the lawyer had embraced his client’s cause to the point, it seems, of sacrificing all objectivity in the appreciation of the situation (I suppose, for that matter, that in his eyes, he was not personally involved. It goes without saying that specimens such as Descôteaux, infra, note 31, or Belhassen, supra, note 17, present a quite different picture, marked by obvious dishonesty. More mundane, but nonetheless disquieting, is an example like Marchand (Litigation guardian of) v. Public General Hospital of Chatham (2000), 51 O.R. (3d) 97 (C.A.), where there is neither querulousness nor dishonesty, but a persistent and reciprocal hostility between the lawyers, reproved by the Court of Appeal of Ontario in these terms (§§ 5 et 169): “The trial was characterized by an extraordinary level of rancour and hostility on the part of counsel, all of whom were, regrettably, senior members of the bar of Ontario. It was not a trial of which the administration of justice can be proud. [...] The trial judge cannot be criticized, let alone be found guilty of judicial bias, for his occasional mild rebuke to counsel.”

|

|

Pathologie et Thérapeutique du Plaideur 175 |

Pathology and Therapeutic of the Litigant 175 |

|

arriver à ses fins, la fin justifiant par ailleurs les moyens. Ces comportements sont depuis longtemps suspects mais ces dernières années on trouve plusieurs décisions administratives et judiciaires qui les censurent sévèrement21. |

achieve his ends, the ends moreover justifying the means. These behaviours have long been suspect, but in recent years, a number of administrative and judicial decisions are found which censure them severely21. |

|

Prenons un exemple qui a connu un certain retentissement: le cas Parizeau. Deux dossiers concernant ce membre du Barreau ont tour à tour défrayé la chronique: l’affaire Gravel c. Parizeau22, sur laquelle la Cour d’appel s’est récemment prononcée23, et qui avait donné lieu à une péripétie parallèle elle aussi assez riche d’enseignements24, et l’affaire Barreau du Québec c. Parizeau25. Abordons d’abord ce second dossier, qui est de nature disciplinaire. L’avocate y est reconnue coupable s’avoir confectionné une fausse preuve, de l’avoir produite, d’en avoir tiré avantage, d’avoir détruit une preuve documentaire, d’avoir incité quelqu’un au parjure et d’avoir introduit devant les tribunaux des réclamations exagérées (la plainte fait état d’une guérilla judiciaire). Tous ces faits s’inscrivaient dans le cadre d’une stratégie judiciaire de surenchère assez caractéristique et que dénonce éloquemment le Comité de discipline26 Mais l’autre dossier, civil celui-là, est peut-être encore plus lourd. Condamnée par la Cour d’appel à verser un dédommagement de 77,500S à sa cliente, l’avocate y est trouvée responsable d’avoir convaincu cette dernière d’adopter en prévision de sa demande de divorce un train de vie très au-dessus de ses moyens financiers réels, stratégie qui d’ailleurs échouera et contribuera à la ruine de la cliente en question. Les motifs de la Cour d’appel donnent à réfléchir27 car ils exposent de la |

Let’s take an example which has become more sporadic: the case of Parizeau. Two files, one after the other concerning this member of the Bar, have unfurled the story: the case of Gravel v. Parizeau22, on which the Court of Appeal recently pronounced23, and which had led to another parallel promenade, itself also richly instructive24, and the case of Barreau du Québec v. Parizeau25. We’ll start with the second file, disciplinary in nature. The lawyer in that file was found guilty of having fabricated false evidence, of having produced it and gained an advantage from it, of having destroyed documentary evidence, of having incited someone to perjury and of having introduced exaggerated claims into the courts (the complaint recounts a legal guerilla war). All these facts entered into the framework of a fairly characteristic legal strategy of overkill and which the Disciplinary Committee eloquently denounced26. But the other file, this one civil, is perhaps even weightier. Condemned by the Court of Appeal to pay damages of $77,500 to her client, the lawyer was found liable for having persuaded him, in light of his application in divorce, to adopt a lifestyle far below his true financial means, a strategy which moreover failed and contributed to the ruin of the client in question. The grounds of the Court of Appeal are food for thought27 because they expose the |

|

21. Ainsi, voir Avocats (Ordre professionnel des) c. Olariu, [1999] D.D.O.P. 85, confirmé par une décision encore inédite du Tribunal des professions.

|

21. On this point, see Avocats (Ordre professionnel des) v. Olariu, [1999] D.D.O.P. 85, confirmed by a still unpublished decision of the Tribunal des professions.

|

|

176 Développements Récents En Déontologie |

176 Recent Developments in Professional Ethics |

|

part de l’avocate en question une manœuvre qui, toute chose égale d’ailleurs, ne pouvait qu’envenimer fortement la contestation dans l’instance où elle occupait. Que peut-on attendre, en effet, d’un défendeur faisant face à une réclamation de plusieurs millions de dollars lorsqu’il est acquis que la réclamation en question est hors de toute proportion avec les actifs véritables de ce défendeur? Ce même procédé de surenchère avait été employé dans le dossier qui s’était soldé par l’instance disciplinaire évoquée plus haut. |

the lawyer in question a manœuvre which, all else being equal, could only seriously embitter the dispute in the instance she occupied. What can one expect, in fact, from a defendant faced with a claim of several million dollars when it is established that the claim in question is out of all proportion to the true assets of this defendant? This same process of exaggeration had been used in the file which ended in the disciplinary action mentioned above. |

|

Au-delà du fait divers, on décèle ici une autre forme d’abus de procédure. Selon toute vraisemblance, un tel abus ne met qu’indirectement en cause le sujet de droit et, sans collusion de la part de ce dernier, ne pourrait que difficilement faire l’objet d’un recours distinct pour abus de droit contre la personne ainsi représentée par son avocat (mais voir le § 5 b) ci-dessous). Ce sont du reste les circonstances inusitées de l’affaire Gravel, et spécifiquement la faillite de la cliente, qui menèrent le dossier devant le tribunal et fournirent à la Cour d’appel l’occasion de dénoncer en termes on ne peut plus explicites la stratégie agressive et mensongère adoptée en demande. |

The various facts aside, another form of abuse of procedure is observed here. To all appearances, such an abuse only indirectly implicates the litigant in the file and, in the absence of collusion by the latter, could only with difficulty be the subject of a distinct recourse for abuse of right against the person represented thusly by her lawyer (however, see § 5b below). This is aside from the rare circumstances in the Gravel case, and specifically the bankruptcy of the client, which brought the file before the court and provided the Court of Appeal with the opportunity to denounce in terms that could not be more explicit the aggressive and deceitful strategy adopted in the claim. |

|

Bien entendu, il peut arriver aussi que l’avocat et son client soient également à blâmer pour une ou plusieurs procédures abusives. Il est souhaitable, dans une telle hypothèse, que le tribunal prenne soin de déposer le blâme partout où il revient, et qu’il censure Ia conduite de l’avocat comme celle de là partie représentée par lui28 |

Of course, it can also happen that the lawyer and his client are equally to blame for one or more abusive procedures. It is desirable, on such an assumption, that the court take care to lay the blame everywhere it belongs, and that it censure the conduct of the lawyer as well as that of the party he represents.28 |

|

place d’un stratagème pour maquiller une situation de faits et tromper le tribunal. Cette faute engagera sa responsabilité si les autres facteurs de lien de causalité et de dommages sont établis. En l’espèce, je ne doute pas que cette faute est prouvée à l’endroit de Me Parizeau.

52. Aussi, en l’espèce, comme le juge de la Cour supérieure, je suis d’avis que Me Parizeau a commis une faute très grave en faisant croire à sa cliente qu’elle devait maintenir et surtout faire voir un haut train de vie ce qui était le gage de l’obtention de mesures accessoires généreuses à l’occasion de son divorce. » |

of a stratagem to mask a de facto situation and to mislead the court. This fault will engage his responsibility if the other factors of the causal link and damages are established. In this case, I do not doubt that this fault is proven with respect to Maître Parizeau.51. To that is added the manner in which the procedures were conducted. Indeed, in order to conform to the strategy that had been worked out, it was necessary to claim large sums, which is what the lawyer did: 6 million as compensation, 1 million in a lump sum and $240,000 as alimony. Nothing in the file justified such a claim. If this procedure had solely as its object to adjust itself to the plan elaborated, it had, in addition, the effect of maintaining the client under the illusion of a real and fast profit. Had not the client to lay out the balance of $320,000 for the acquisition of his apartment 24 months after signature of the contract?52. Also, in the circumstances, like the judge of the Superior Court, I am of the opinion that Maître Parizeau committed a serious misconduct in letting her client believe that the latter must maintain and above all be seen maintaining an elevated lifestyle, as the standard for obtaining generous accessory measures at the time of his divorce.” |

|

28. Ainsi, voir Calais Development Inc. v.Drazin, [1999] J.Q. No. 5791 (C.S.), particulièrement aux ¶¶ 170 à 202 et 203 à 207. |

28. Ergo, see Calais Development Inc. v. Drazin, [1999] J.Q. No 5791 (C.S.), particularly at ¶¶ 170 to 202 and 203 to 207. |

|

Pathologie et Thérapeutique du Plaideur 177 |

Pathology and Therapeutic of the Litigant 177 |

|

3. Aspects institutionnels et systémiques: l’inflation litigieuse |

3. Institutional and systemic aspects: litigious inflation |

|

Sans doute faut-il distinguer pour les fins de l’analyse entre, d’une part, les attributs du sujet de droit, parfois lui-même auteur de l’abus et, d’autre part, le comportement de son avocat. Mais, à trop insister sur cette distinction, on en vient à perdre de vue certains autres aspects de l’abus de procédure: le rapport qui existe entre le comportement abusif et le cadre dans lequel s’ïnsère la procédure29. |

Undoubtedly, for the purposes of the analysis undertaken, one must distinguish on the one hand, the attributes of the subject of the law, himself sometimes the author of the abuse and, on the other hand, the behavior of his lawyer. But, to overly insist upon this distinction, is to lose sight of certain other aspects of the abuse of procedure: the connection which exists between the abusive behavior and the framework into which the procedure is inserted29. |

|

Revenons brièvement sur la perspective du sujet. Comme le soutenait récemment un auteur dans une discipline autre que le droit, au plan subjectif, la réceptivité à la plainte l’attise et l’exacerbe30. Lever les obstacles qui feraient échec au plaideur quérulent l’encouragera à persister dans ses entreprises litigieuses31. Cette hypothèse, qui parait a priori plausible, a des implications surprenantes. Ainsi, on peut avancer que, plus l’on facilite l’accès à la justice, plus l’on facilite l’abus de procédure. Et je crois que cette hypothèse se vérifie parfois dans les faits. |

Let us briefly come back to the perspective of the subject. As recently asserted by an author in a discipline other than the law, on the subjective plane, receptivity to the complaint fans the flames and exacerbates it30. To remove the obstacles which would obstruct the querulous litigant will encourage him to persist in his litigious enterprises31. This assumption, which appears a priori plausible, has surprising implications. One can thus advance that, the more one facilitates access to justice, the more one facilitates the abuse of procedure. And I believe that this hypothesis is sometimes proven by the facts. |

|

Donnons quelque faits simples. Ma Faculté participe depuis trois ans avec la Faculté de droit de l’Université de Montréal et la magistrature canadienne à un projet financé par l’ACDI dont l’objet est de former des juges de la République populaire de Chine. Dans le cadre de ce projet, des groupes d’une vingtaine de juges chacun passent plusieurs mois à Montréal en stage de formation et plusieurs juges et professeurs canadiens prennent part à des missions de formation en Chine. Participant à ces activités, j’ai demandé à certains de ces juges, dont je dirigeais des travaux de recherche ou à qui j’enseignais, comment le problème de l’abus de procédure est abordé |

Let’s take a few simple facts. My Faculty has taken part for three years with the Faculty of Law of the University of Montreal and the Canadian magistrature in a project financed by the ACDI, whose object is to train judges in the People’s Republic of China. Within the framework of this project, groups of a score of judges each spend several months in Montreal in training and a number of Canadian judges and professors take part in training missions in China. Participating in these activities, I asked some of these judges, whom I taught or whose research tasks I supervised, how the problem of abuse of procedure is tackled |

|

29. À mon avis, cette relation va bien au-delà des considérations qui seront mentionnées ici et elle atteint la définition même de ce qui est abusif: bien des initiatives judiciaires sont acceptées aux États-Unis (et en particulier dans les Etats où les affrontements judiciaires sont le plus prisés, comme le Texas) qui paraîtraient insensées ou abusives au Canada. |

29. In my opinion, this relation is well beyond the considerations which will be mentioned here and it even touches on the very definition of that which is abusive: many legal initiatives are accepted in the United States (and in particular in States where legal confrontations are the most prized (intense?), such as Texas) which would seem foolish or abusive in Canada. |

|

30. En restant sourd à la plainte, on force le sujet à prendre du recul, et cet effet de distanciation peut être salutaire. Voilà en une douzaine de mots le noyau dur d’une thèse présentée par le psychanalyste et philosophe François Roustang dans La fin de la plainte, Paris, Éditions Odile Jacob, 2000: « Il faut en finir avec la plainte, sortir de notre moi chéri, que nous cultivons à coup de jérémiades. » |

30. By turning a deaf ear to the complaint, one forces the subject to retreat, and this distancing effect can be salutary. There, in a dozen words, is the hard core of a thesis presented by the psychoanalyst and philosopher François Roustang in La fin de la plainte [The End of the Complaint], Paris, Éditions Odile Jacob, 2000: “It is necessary to end the complaint, to exit from our cherished “me”, that we cultivate with the blows of angry lamentations.” |

|

31. Aussi a-t-on pu soutenir que les revendications de plus en plus déraisonnables de Fabrikant, avant comme pendant son procès, s’intensifiaient en raison même de l’absence de limite, voire de l’anomie, propre au cadre dans lequel il évoluait: voir Mathieu BEAUREGARD, La folie de Fabrikant, Paris/Montréal, L’Harmattan, 1999, p. 113-117 et 122. |

31. Likewise, it was possible to argue that the increasingly unreasonable claims of Fabrikant, before as well as during his lawsuit, intensified because of this very absence of a limit, even anomie, specific to the framework in which he evolved: see Mathieu BEAUREGARD, La folie de Fabrikant [The Folly of Fabrikant], Paris/Montreal, Harmattan, 1999, p. 113-117 and 122. |

|

178 Développements Récents En Déontologie |

178 Recent Developments in Professional Ethics |

|

dans leur système juridique. Ils n’ont pas compris la question que je leur posais et l’incompréhension ne se situait pas au niveau lexical. II semble en effet qu’en Chine l’abus de procédure ne soit pas problématisé en droit positif. Sans doute y a-t-il d’autres problèmes pressants, réclamant une solution, comme celui beaucoup plus fondamental, j’en conviens, des difficultés d’accès à la justice, mais l’abus de procédure n’est pas de ceux-là. |

in their legal system. They didn’t understand the question that I had posed to them and the incomprehension was not at the lexical level. It seems indeed that in China, abuse of procedure is not problematic in substantive law. Undoubtedly there are other pressing problems, requiring a solution, such as that much more fundamental, I agree, of the difficulties of access to justice, but the abuse of procedure is not among them. |

|

Dans le même ordre d’idées, mais cette fois-ci en inversant le raisonnement, la possibilité qui est faite aux particuliers (dans le Code des professions)32 (ou, antérieurement, dans certaines lois professionnelles) de porter devant un comité de discipline professionnelle une plainte contre un membre d’un ordre professionnel ouvre la porte à l’abus. Certes, l’existence de tels abus n’est pas un argument pour rétablir le régime antérieur, en vertu duquel toutes les plaintes devaient provenir d’un syndic. Mais on trouve ici et là des cas d’abus de procédure qui laissent soupçonner de la part du plaignant privé une sérieuse propension à la querulence33. Dans un cas, même, cette conclusion est pour ainsi dire avérée34. Il y a d’ailleurs une noire |

In the same way, but this time by reversing the reasoning, the possibility offered to private individuals (in the Code of Professions) 32 (or, previously, in certain professional laws) of bringing a complaint against a member of a professional order before a professional disciplinary committee, opens the door to abuse. Admittedly, the existence of such abuses is not an argument to restore the previous regime, in virtue of which all complaints were to come from a syndic. But one finds here and there cases of abuse of procedure which lead to suspect, on the part of the private plaintiff, a serious propensity for querulence33. In one case, this conclusion is so-to-speak, proven34. There is moreover a black |

|

32. C’est ce que prévoit maintenant l’article 128 du Code des professions, L R Q . c. C-26. |

32. This is what Section 128 of the Code of Professions, L.R.Q. C. C-26, now provides. |

|

33. Voir et comparer, en ce qui concerne le Barreau, Hamelin c. Piché et Joyal, [1991] D.D.A.N. No. 68 et Carter c. de Wolfe, [1994] D.D.A.N. No. 113 (où des plaintes non fondées semblent avoir été portées par des clients mal conseillés), ainsi que De Niverville c. Descôteaux, [1997] A.Q. No. 448 (C.S.) (où la partie requérante obtient une injonction pour mettre fin à une quantité des plaintes abusives), avec Demarco c. Tellier, [1994] D.D.A.N. No. 50, et Fecteau c. Marcotte, [1994] D.D.A.N. No. 118 (où l’hypothèse de la quérulence est beaucoup plus plausible). Les avocats ne sont cependant pas les seules victimes potentielles de ces abus: voir Guertin c. Field, [1998] D.D.O.P. 45 (plainte privée «mal fondée, farfelue et de mauvaise foi» contre un comptable). |

33. See and compare, with regard to the Bar, Hamelin v. Piché and Joyal, [1991] D.D.A.N. No 68 and Carter v. de Wolfe, [1994] D.D.A.N. No 113 (where nonfounded complaints seem to have been brought by poorly advised clients), as well as Niverville v. Descôteaux, [1997] A.Q. No 448 (C.S.) (where the applicant obtains an injunction to put an end to a quantity of abusive complaints), with Demarco v. Tellier, [1994] D.D.A.N. No 50, and Fecteau v. Marcotte, [1994] D.D.A.N. No 118 (where the assumption of querulence is much more plausible). Lawyers, however, are not the only potential victims of these abuses: see Guertin v. Field, [1998] D.D.O.P. 45 (private complaint ill-founded, farfetched and in bad faith against an accountant). |

|

34. Il s’agit de l’affaire Barreau du Québec c. Siminski, [1999] J.Q. No. 1568, JE. 99-1173 (C.S.). où le Barreau du Québec obtient contre l’intimé une injonction dont l’effet serait sensiblement le même que celui des ordonnances accordées dans les affaires Yorke ou Byer, infra. Siminski, insatisfait d’un jugement de divorce, (¶ 9) «s’est porté demandeur, requérant, plaignant et appelant dans une suite quasi-interminable de procédure, judiciaire ou disciplinaire, depuis 1981». Le juge Paul Chaput écrit: (¶ 33) «C’est à croire qu’il fait des recours en justice son occupation à temps plein.» Ce comportement avait un impact sur le fonctionnement de l’institution: (¶¶ 36-37) «[...] de l’escalade des actions et recours entrepris par F. Siminski, il peut résulter à toutes fins pratiques l’asphyxie des instances disciplinaires du Barreau. Dès que F. Siminski est l’objet d’une décision qu’il n’aime pas, qu’elle le concerne lui ou des tiers, il dépose des plaintes ou des actions en dommages, qui sont presque inévitablement rejetées. – Comme les membres des instances disciplinaires du Barreau agissent bénévolement, on comprend la difficulté du Barreau à les recruter. Les avocats et avocates sont réticents à y plaider, sachant qu’ils seront probablement les prochains intimés ou défendeurs recherchés par F. Siminski.» |

34. This is the matter of Barreau du Quebec v. Siminski, [1999] J.Q. No 1568, J.E. 99-1173 (C.S.). where the Bar of Quebec obtains an injunction against the respondent the effect of which would be appreciably the same as that of the ordinances granted in the cases of Yorke or Byer, will infra. Siminski, dissatisfied with a judgment in divorce, (¶ 9) “went petitioning, as applicant, plaintiff and appellant in a quasi-interminable series of procedures, judicial and disciplinary, since 1981”. Judge Paul Chaput wrote: (¶ 33) “It is to be believed that he makes appeals to justice his full-time occupation.” This behavior had an impact on the functioning of the institution: (¶¶ 36-37) “[...] from the escalation of actions and recourses undertaken by F. Siminski, can result, for all practical purposes, the asphyxiation of the disciplinary authorities of the Bar. As soon as F. Siminski is the object of a decision which he does not like, whether it relates to him or to third parties, he files complaints or actions in damages, which almost inevitably are rejected. – As the members of the disciplinary authorities of the Bar are volunteers, one understands the difficulty of the Bar in recruiting them. The lawyers are reticent to plead there, knowing that they probably will be the next respondents or defendants pursued by F. Siminski.” |

|

Pathologie et Thérapeutique du Plaideur 179 |

Pathology and Therapeutic of the Litigant 179 |

|

ironie dans le fait que le client quérulent semble être par excellence le client de l’avocat, avant de se retourner contre lui pour devenir son adversaire et son contempteur 35, – pourquoi d’ailleurs s’en étonner? |

irony in the fact that the querulous client seems to be par excellence the client of the lawyer, before turning against him to become his adversary and his despiser35, – why the surprise, moreover? With regard to abuse of procedure as elsewhere, opportunity makes the thief. |

|

Une manière de réduire le nombre de recours abusifs consiste à assujettir tous les recours d’un certain type, ou certains d’entre eux lorsqu’ils sont exercés par des plaideurs identifiés, à un contrôle préalable. La requête pour permission d’appeler est de cet ordre et il en allait de même à une certaine époque pour les recours extraordinaires en deux étapes soumis à la nécessité de l’autorisation préalable d’un juge 36. Divers procédés sont .utilisés pour prévenir l’engorgement des tribunaux ou la congestion des rôles qui peuvent aussi servir à filtrer les recours abusifs. Mais, plus la porte est grande ouverte, plus il y aura place à l’abus. |

One way of reducing the number of abusive recourses consists in subjecting all recourses of a certain type, or some of them when they are exerted by identified litigants, to preliminary control. The motion for permission to appeal is of this order, and that was how it went, at a certain era, for extraordinary recourses in two stages submitted to the necessity of the prior authorization of a judge. 36 Various procedures are utilized to prevent overloading of the courts or congestion of the roles which may also serve to filter the abusive recourses. But, the wider the door is opened, the more room there is for abuse. |

|

Quelques éléments de droit comparé jettent un peu plus de lumière sur cette question. Pensons à l’exemple de la Cour de cassation française. On connaît au Québec certains grands arrêts de cette haute juridiction mais on connaît moins son mode de fonctionnement. La Cour de cassation se situe au sommet de la hiérarchie judiciaire française. Elle a compétence sur les affaires civiles (entendues au sens large et comprenant les affaires commerciales, financières et sociales), ainsi que sur les affaires criminelles. Elle compte environ 150 magistrats du siège. Or, elle dispose en moyenne de deux à trois dizaines de milliers d’affaires par année. Elle en a jugé 26 786 en 1997, 26 687 en 1998 et 29 071 en 1999; au 31 décembre 1999, 40 586 dossiers restaient à juger, une augmentation de 26,34% par rapport à 1988 où 32 134 affaires étaient en instance 37. Il faut savoir aussi que, sauf désistement, la Cour de cassation doit donner réponse à toutes les demandes des justiciables et qu’elle ne fait aucun choix dans les |

A few elements of comparative law throw a little more light on this question. Think of the example of the French Court of Appeal. In Quebec certain great judgments of this august jurisdiction are familiar, but less is known about its functioning. The Court of Appeal is located at the top of the French legal hierarchy. It is competent in civil cases (heard in the broad sense and including commercial, financial and social matters), as well as in criminal cases. It counts approximately 150 sitting magistrates. However, it has on average two to three dozens of thousands of cases per year. The Court adjudicated 26,786 files in 1997, 26,687 in 1998 and 29,071 in 1999; as at December 31st, 1999, 40,586 files remained to be adjudicated, an increase of 26,34% compared to 1988 when 32,134 matters were pending37. It also should be known that, aside from withdrawals, the Court of Appeal must respond to all requests of those involved and that it does not choose the |

|

35. Voir par exemple Fecteau c. Genest, [1994] D.D.A.N. No. 106: «Cette attitude n’est pas nouvelle, elle a été la source de la majorité des problèmes que M. Fecteau a connus avec tous les avocats à qui il a demandé de le représenter, soit Me Jules Bernatchez, Me Marc Gilbert, Me Manon Leclerc, Me Robert Marceau, Me Guylaine Marcotte, Me Gaétan Marineau, Me Michel Moreau, Me Sophie Noël, Me Daniel Petit et Me Denis Richard. Des plaintes disciplinaires ont été déposées par le plaignant contre tous et chacun des avocats et avocates précités et tous ont été acquittés par le présent Comité qui a constaté que l’attitude de M. Fecteau a toujours été la cause du refus de ces avocats de le représenter.» |

35. See for example Fecteau v. Genest, [1994] D.D.A.N. No 106: “This attitude is not new, it was the source of the majority of the problems that Mr. Fecteau had with all the lawyers whom he asked to represent him, that is to say Maître Jules Bernatchez, Maître Marc Gilbert, Maître Manon Leclerc, Maître Robert Marceau, Maître Guylaine Marcotte, Maître Gaetan Marineau, Maître Michel Moreau, Maître Sophie Noël, Maître Daniel Petit and Maître Denis Richard. Disciplinary complaints were filed by the plaintiff against every one of the above-mentioned lawyers and all were discharged by this Committee which noted that the attitude of Mr. Fecteau was always the cause of the refusal of these lawyers to represent him.” |

|

36. Voir la Note des commissaires dans le Code de procédure civile de 1965, présentant les dispositions générales (art. 834-847) du Titre VI du Code. |

36. See the Commissioners’ Note in the Code of Civil Procedure of 1965, presenting the general provisions (ss. 834-847) of Title VI of the Code. |

|

37. Ces chiffres proviennent de diverses sources toutes accessibles par le site Internet de la Cour de cassation: http://www.cour de cassation.fr. |

37. These figures come from a variety of sources all accessible from the web site of the Court of Appeal: http://www.cour de cassation.fr. |

|

180 Développements Récents En Déontologie |

180 Recent Developments in Professional Ethics |

|

pourvois. Elle est donc constamment vulnérable à l’inflation litigieuse. Le 6 janvier 2000, le Premier président de la Cour de cassation, monsieur Guy Canivet, prononçait à l’occasion de l’audience solennelle de rentrée un discours où il déplorait cette situation. Parmi trois solutions possibles38 il évoquait le contrôle par la profession des avocats39 et le filtrage des pourvois par la Cour40. |

appeals. It is thus constantly vulnerable to litigious inflation. On January 6th, 2000, the First President of the Court of Appeal, Mr. Guy Canivet, in his speech at the formal opening of the new legal year, deplored this situation. Among three possible solutions38 he evoked control by the legal profession39 and filtering of appeals by the Court40. |

|

Un dernier aspect, celui-ci franchement «systémique» plutôt qu’institutionnel, vaut enfin d’être mentionné sous la même rubrique. Si à un extrême le long d’un même continuum, on trouve le plaideur quérulent qui inflige à autrui un feu nourri de recours abusifs, on trouve aussi à l’autre extrême des sociétés plus litigieuses que d’autres, des sociétés où le recours aux tribunaux sera nettement plus fréquent et se fera de manière nettement plus agressive qu’ailleurs: bref, des sociétés qu’on peut qualifier de litigieuses, où sera considéré comme normal et banal ce qui apparaîtrait intempestif et peut-être même abusif en un autre endroit. On commence à peine à explorer les différences de ce genre mais il se fait certains travaux en analyse économique du droit qui méritent de retenir l’attention (la question des recours abusifs dans une perspective autre que comparative a par ailleurs déjà fait l’objet de beaucoup de travaux théoriques et empiri- |

A last aspect, this one frankly “systemic” rather than institutional, is finally worth mentioning under the same heading. If at the far extremity of the same long continuum, one finds the querulous litigant who inflicts upon others a heavy barrage of abusive recourse, one finds at the other extreme societies more litigious than others, societies where recourse to the courts will be definitely more frequent and will be done in a way definitely more aggressive than elsewhere: in short, societies that one can describe as litigious, where that will be regarded as normal and banal which appears inopportune and perhaps even abusive in another place. Differences of this kind have barely begun to be explored, but certain works of economic analysis of law which merit attention (the question of abusive recourses from a perspective other than comparative has moreover already been the subject of many theoretical and empiri- |

|

38. Je n’insisterai pas sur la troisième solution proposée, qui ne concerne pas l’abus de droit. Elle consisterait à augmenter les effectifs de la Cour jusqu’à ce que fatalement, ajoutait M. Canivet, infra, «ces moyens libérés s’avèrent bientôt insuffisants du fait d’une nouvelle augmentation du nombre des recours.» |

38. I will not emphasize the third solution suggested, which does not relate to the abuse of right. It would consist of increasing the manpower of the Court until fatally, Mr. Canivet added, infra, “these added means soon prove insufficient because of a new increase in the number of recourses.” |

|

39. Cette hypothèse est réaliste dans le cas précis de cette institution car il faut savoir qu’un corps restreint (l’Ordre des avocats au Conseil d’État et à la Cour de cassation, connus aussi comme les avocats aux Conseils) a le monopole de la représentation devant la Cour. Sauf en matières pénales et sociales, où les parties ne sont pas obligées de se constituer un avocat, toute affaire doit passer par un avocat membre de l’Ordre. Bien qu’ils puissent employer des collaborateurs, en mars 2000 ils n’étaient en tout et pour tout que 86, ce qui ne peut que renforcer la cohésion du groupe et sa loyauté envers l’institution. |

39. This assumption is realistic in the precise case of this institution because it should be known that a restricted body (the Order of lawyers to the Council of State and the Court of appeal, known also as lawyers to the Councils) has the monopoly of representation before the Court. Other than for penal and social matters, where the parties are not obliged to constitute a lawyer, all business must pass through a lawyer member of the Order. Although they can employ collaborators, in March 2000 these numbered in all only 86, which can only reinforce the cohesion of the group and its loyalty to the institution. |

|

40. Voir http://www courdecassation.fr/_actualite/actualite.htm: «Une autre possibilité [...] obligerait chaque partie, dans tous les cas, même en matière sociale et pénale, à constituer un avocat au Conseil pour former et soutenir un pourvoi. On y voit, avec beaucoup de réalisme, un moyen de réduire le nombre des dossiers, tout en rétablissant, entre les parties, une égalité des chances dans le procès en cassation. Toutefois, afin de ne pas créer une rupture d’égalité financière d’accès à la Cour, il serait nécessaire d’adapter le système d’aide juridictionnelle selon des modalités dont le coût est à évaluer puis d’instaurer une concertation avec les groupes socio-professionnels concernés. (…) Enfin, un moyen éprouvé quant à ses résultats par la pratique qu’en ont la plupart des juridictions de cassastion, consiste à donner des réponses judiciaires diversifiées selon le sérieux des critiques formulées contre la décision attaquée, selon l’intérêt et l’importance de la question juridique posée. Il est pour cela indispensable que la Cour renforce son dispositif d’examen préalable des pourvois et que soient réinstituées des procédures de filtrage permettant de ne pas admettre ceux qui, à l’évidence, ne sont fondés sur aucun moyen sérieux.» |

40 See http://www courdecassation.fr/_actualite/actualite.htm: ““Another [...] possibility would oblige each party, in all cases, even in social and penal matters, to constitute a lawyer with the Council to institute and support an appeal. Here, one sees, with a great deal of realism, a means of reducing the number of files, while restoring, between the parties, an equal opportunity in the lawsuit in appeal. However, in order not to create a rupture in equality of financial access to the Court, it would be necessary to adapt the system of jurisdictional aid according to a scale where the cost is to be evaluated, then to found a dialog with the socio-professional groups concerned. (…) Lastly, a means tested as to its results by practice in most of the appeal jurisdictions, consists in giving diversified legal responses according to the seriousness of the criticisms formulated against the decision under attack, according to the interest and the importance of the legal question posed. For this, it is essential that the Court reinforce its system of prior review of appeals and that filtering procedures be re-established making it possible to exclude those which, obviously, are not founded on any serious ground.” |

|

Pathologie et Thérapeutique du Plaideur 181 |

Pathology and Therapeutic of the Litigant 181 |

|

ques en analyse économique du droit américain41, leur objet étant le plus souvent de circonscrire le recours abusif à partir de critères qualifiés de game-theoretic; je ne suis pas sûr pour ma part que le postulat de rationalité des acteurs en théorie des jeux fasse bon ménage avec la réalité observée, soit celle du plaideur quérulent ou de l’avocat vénal). |

cal works of economic analysis of American law41, their object most often being to circumscribe the abusive recourse on the basis of qualified criteria from game theory; as for myself, I am not sure that the postulate of rationality of the actors in game theory plays well with the observed reality, either that of the querulous litigant or of the venal lawyer). |

|

Ainsi, dans The Problematics of Moral and Legal Theory42, Richard A. Posner s’est intéressé aux différences qui existent sur ce plan entre les États-Unis et l’Angleterre, ainsi qu’à celles qui existent entre Etats américains. Il n’est guère contesté que les Etats-Unis soient une société plus litigieuse que beaucoup d’autres. Bien qu’en Angleterre et aux États-Unis le droit matériel ou droit du fond soit substantiellement semblable dans des domaines comme les contrats et la responsabilité civile, il y a entre ces deux pays des différences frappantes dans les tendances litigieuses, la porportion de poursuites en responsabilité civile per capita étant trois fois plus élevée aux États-Unis qu’en Angleterre. Or, cette différence est encore plus marquée entre les États américains eux-mêmes: on observe une moyenne de 97,2 poursuites civiles par tranche de 100 000 habitants au Nord Dakota, contre 1 070,5 poursuites par tranche au Massachusetts (la moyenne est de 133,5 en Angleterre). Ces différences, ajoute-t-on, sont beaucoup plus importantes que celles que l’on peut relever entre les coûts de la justice ou la fréquence des accidents dans chaque État. |

Thus, in The Problematics of Moral and Legal Theory42, Richard A. Posner was interested in the differences which exist from this point of view between the United States and England, as well as with those which exist between American States. It is hardly disputed that the United States is a more litigious society than many others. Although in England and in the United States the material law or basic law is substantially similar in areas such as contracts and civil liability, there are between these two countries striking differences in litigious tendencies, the porportion of suits in civil liability per capita being three times higher in the United States than in England. However, this difference is even more marked between the American States themselves: one observes an average of 97.2 civil suits per sample of 100,000 inhabitants in North Dakota, versus 1,070.5 suits per sample in Massachusetts (the average is 133.5 in England). These differences, in addition, are much bigger than those which one can deduce from the costs of justice or the frequency of accidents in each State. |

|

Pourquoi en est-il ainsi? On attribue souvent de telles différences à des facteurs culturels43 mais Posner tente de préciser l’analyse. Il utilise des régressions pour mettre en relation divers facteurs: 1. le taux de morts accidentelles pour chaque État, 2. le taux d’urbanisation (pertinent parce que, dans un État fortement urbanisé, une proportion beaucoup plus élevée d’accidents implique des parties qui ne |

Why is this the case? One often attributes such differences to cultural factors,43 but Posner tries to sharpen the analysis. He uses regressions to connect various factors: 1. the rate of accidental deaths for each State, 2. rates of urbanization (relevant because, in a strongly urbanized State, a much higher proportion of accidents implies that parties who do not |

|

41. Ainsi, voir Robert G. BONE, «Modeling frivolous suits», (1997) 145 University of Pensylvania Law Review 519; Linda R. MEYER, «When reasonable minds differ», (1996) 71 New York University Law Review 1467; Charles M. YABLON, «The good, the bad, and the frivolous case: an essay on probability and Rule 11», (1996) 44 UCLA Law Review 65; Warren F. SCHWARTZ et C. Frederick BECKNER III, «Toward a theory of the «meritorious case»: legal uncertainty as a social choice problem», (1998) 6 George Mason Law Review 801; James W. MACFARLANE, «Frivolous conduct under Model Rule of Professional Conduct 3.1», ( 1996-7) 21 The Journal of the Legal Profession 231; Cari TOBIAS. «Some realism about empiricism», (1994) 26 Connecticut Law Review 1093. |

41. Also see Robert G. BONE, “Modeling frivolous suits”, (1997) 145 University of Pensylvania Law Review 519; Linda R. MEYER, “When reasonable minds differ”, (1996) 71 New York University Law Review 1467; Charles M. YABLON, “The good, the bad, and the frivolous case: an essay on probability and Rule 11″, (1996) 44 UCLA Law Review 65; Warren F. SCHWARTZ et C. Frederick BECKNER III, “Toward a theory of the ‘meritorious case’: legal uncertainty as a social choice problem”, (1998) 6 George Mason Law Review 801; James W. MACFARLANE, “Frivolous conduct under Model Rule of Professional Conduct 3.1″, ( 1996-7) 21 The Journal of the Legal Profession 231; Cari TOBIAS. “Some realism about empiricism”, (1994) 26 Connecticut Law Review 1093. |

|

42. Cambridge Mass., Harvard University Press. 1999, p. 217 et s. |

42. Cambridge Mass., Harvard University Press. 1999, p. 217 et seq. |

|

43. Parmi bien d’autres exemples, voir Oscar G. CHASE, «Culture and Disputing», (1999) 7 Tulane Journal on International and Comparative Law 81, pour la description d’une approche ethnologique. |

43. Among many other examples, see Oscar G. CHASE, “Culture and Disputing”, (1999) 7 Tulane Journal on International and Comparative Law 81, for the description of an ethnological approach. |

|

182 Développements Récents En Déontologie |

182 Recent Developments in Professional Ethics |

|

se connaissent pas, et la concentration d’avocats est beaucoup plus forte dans les zones urbaines), 3. la densité démographique (plus elle est élevée, plus la probabilité que les parties se connaissent est faible), 4. le taux de scolarisation (ou la moyenne des années d’études par habitant), 5. le revenu moyen des ménages, 6. le taux de protection assurantielle (les régimes étatisés devant évidemment figurer dans l’équation), 7. le nombre d’avocats per capita. Bien que l’étude ne soit pas concluante sur un plan empirique, comme le concède Posner lui-même, elle fait ressortir des corrélations susceptibles de surprendre le lecteur. Ainsi, à taux d’accident égal, une société plus urbanisée, plus scolarisée et dont le revenu per capita est plus élevé sera plus litigieuse. Le litige serait en quelque sorte un bien de luxe, que tout le monde ne peut pas se payer, mais dont certains abusent inévitablement. |

know each other, and the lawyer concentration is much higher in urban areas), 3. demographic density (the higher it is, the more likely it is that the parties do not know each other), 4. rates of schooling (or the average number of years of studies per capita), 5. average household revenue, 6. rates of insuredness (nationalized regimes obviously having to appear in the equation), 7. the number of lawyers per capita. Although the study is not conclusive on an empirical level, as Posner himself concedes, it underscores correlations likely to surprise the reader. Thus, at an equal rate of accidents, a society that is more urbanized, and more educated, and whose per capita income is higher, will be more litigious. Litigation would to some extent be a luxury item, that not everyone can afford, but which some inevitably misuse. |

|

II- Principaux Remèdes |

II- Main Remedies |

|

1. Quelques considérations théoriques |

1. A Few Theoretical Considerations |

|

Avant de considérer certaines des innovations opportunes dont disposent maintenant les parties, les avocats et les tribunaux pour remédier à l’abus de procédure, je voudrais revenir brièvement sur le problème qui avait retenu mon attention dans un article publié en 198444. Je me demandais dans quelle mesure on pouvait conclure à l’existence d’un abus de procédure, et tenter d’y remédier, en examinant seulement le degré d’absurdité d’une proposition de droit ou de fait. On peut supposer, en effet, qu’entre les propositions litigieuses qui sont absurdes de manière patente et celles qui, en dernière analyse, seront validées par les institutions de décision – même de justesse, il existe une gradation dans la précarité des prétentions de fait ou de droit. Lorsque l’on s’éloigne du modèle logico-déductif (une proposition de droit en amont de la décision de justice est vraie ou fausse selon un corpus de raisons qui est déjà en place, et la décision de justice illustre une vérité juridique en procédant selon un raisonnement rigoureusement déductif qui est le fondement sa légitimité) et que l’on se rapproche du modèle téléologico-inductif (une proposition de droit devient vraie ou fausse en aval de la décision de justice qui en dispose, et cette décision constitue – elle crée, en somme – une vérité juridique additionnelle, procédant selon un raisonnement inductif qui demeure légitime puisqu’il faut trouver une issue raisonnable aux litiges en purgeant le droit de ses incertitudes), on fait une place de plus en plus grande à la thèse de l’indétermination. |

Before considering some of the convenient innovations now available to parties, lawyers, and the courts, to remedy the abusive procedure, I would like to briefly reconsider the problem which had held my attention in an article published in 198444. I wondered to what point one could conclude as to the existence of an abuse of procedure, and try to remedy it, by examining only the degree of absurdity of a proposition of law or of fact. One can suppose, indeed, that between litigious propositions which are absurd in an obvious way and those which, in the last analysis, will be validated – even as to their accuracy – by the institutions of decision, there exists a gradation in the precariousness of the claims of fact or law. When one moves away from the logico-deductive model (a proposition of law upstream of the legal decision is true or false according to a corpus of reasons which is already in place, and the legal decision illustrates a legal truth while proceeding according to rigorously deductive reasoning which is the basis of its legitimacy) and as one approaches the teleologico-inductive model (a proposition of law becomes true or false downstream from the legal decision which has disposed of it, and this decision constitutes – it creates, all in all – an additional legal truth, proceeding according to an inductive reasoning which remains legitimate since it is necessary to find a reasonable exit from litigation by purging the law of its uncertainties), one makes more and more room for a theory of indeterminacy. |

|

44. Supra, «L’initiative», note 2. |

44. Supra, «L’initiative», note 2. |

|

Pathologie et Thérapeutique du Plaideur 183 |

Pathology and Therapeutic of the Litigant 183 |

|

II- Principaux Remèdes |

II- Main Remedies |

|

Ce faisant, on accepte que, là où il y a litige, c’est très souvent parce qu’il y a indétermination45 et qu’il n’existe pas de critère de vérité univoque pour résoudre la question litigieuse – sinon, en effet, pourquoi les parties perdraient-elles leur temps à s’affronter dans un litige dont l’issue est déjà presque certaine? Comme de façon générale la théorie du droit depuis au moins trente ans adopte de plus en plus volontiers le modèle téléologico-inductif, il me semblait en 1984 que conclure au caractère abusif d’un recours en fonction uniquement de |

In doing this, we accept that, where there is litigation, it is very often because there is an indeterminacy45 and that no unequivocal criterion of truth exists to resolve the litigious question – if not, indeed, why would the parties waste their time confronting one another in litigation whose outcome is already virtually certain? Since in a general way the theory of law for at least thirty years has more and more readily adopted the teleologico-inductive model, it seemed to me in 1984 that to conclude as to the abusive character of a recourse only as a function of |

|

45. Le rapport entre l’indétermination du droit et les recours abusifs est étudié par Linda R. MEYER dans «When reasonable minds differ», supra, note 41. Bien entendu, l’indétermination des faits ou du droit n’explique pas tout. En ce qui concerne la première, celle des faits, la procédure contradictoire vise à la résorber en faisant la lumière sur ce qui est en litige. Si une question de fait demeure impossible à élucider, le fardeau de la preuve (qui sert à attribuer ce que l’on appelle en anglais the risk of non-proof détermine l’issue du litige: voir parmi quantité d’autres exemples souvent complexes, Poulin c. Prat, [1997] R.J.Q. 2669 (C.A.). En ce qui concerne la seconde, celle du droit, les tribunaux ne répugnent plus, de nos jours, à en officialiser l’existence: voir parexemple Kleinwort Benson Ltd. c. Lincoln City Council, [1998] H.L.J. No. 39. Ce que la Chambre des Lords dit du common law dans cet arrêt me semble également applicable à l’interprétation par le juge, et de la jurisprudence, et de la loi. Aussi est-il dans l’ordre des choses qu’une partie à un litige fou son avocat) mette au service de ses intérêts l’indétermination des faits ou du droit dont elle a connaissance. Tant qu’on ne lui a pas dit qu’elle a tort, libre à elle de penser qu’elle a raison. Cela parait en tout cas de bonne guerre dans un système contradictoire. Si, après coup, l’indétermination est résolue contre elle par le tribunal, la sanction usuelle des dépens devrait suffire à rétablir l’équilibre entre les plaideurs, quitte à pratiquer certains ajustements conformément à l’article 477 C.p.c. Restent cependant les cas où, tout compte fait, aucune personne raisonnable n’aurait conclu à une réelle indétermination des faits ou du droit avant le jugement (je passe ici sur le problème fort délicat de l’absence d’indétermination ex ante, suivie d’un revirement jurisprudentiel ou doctrinal en cours de litige, qui modifie une prémisse essentielle dans la qualification juridique de la situation: voir sur ce point «L’initiative», supra, note 2, p. 454-458, au sujet de l’affaire «Syndicat des employés de l’aluminium de Baie-Comeau» c. «Société canadienne de métaux Reynolds», [1976] C.A. 26). Quand les choses se présentent sous ce jour, il faut envisager de sévir car, à première vue, une personne a profité abusivement du système judiciaire aux dépens d’une autre. Souvent – peut-être même dans la très grande majorité des cas – ces espèces se caractérisent tout simplement par un refus obstiné de se conformer à une règle claire en présence de faits non litigieux, par une fuite devant le droit. Elles relèvent alors de ce que j’ai appelé ailleurs «le syndrome du sabot de Denver» (voir «Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle (la rationalité juridique)», (2000) 45 McGill Law Journal 591,594) ou «les besognes de police» (voir «Figure actuelle du juge dans la cité», ( 1999) 30 Revue de Droit de l’Université de Sherbrooke 1, 28 et note 79) et elles se résolvent par un jugement expéditif dont l’obtention par la partie victime de l’abus ne se solde pas nécessairement par des frais importants. Mais il arrive aussi qu’une partie, en demande ou en défense, élève une contestation insane contre un adversaire, et je définirais comme insane une contestation qui se situe au-delà des limites de l’indétermination. C’est ce que le «procès du procès» servira à déterminer contextuellement. |