Quotations on “Inherent Power” and on “Inherent Jurisdiction”

DRAFT PAGE underway. I have to tidy this up.

Bookmark and check back.

Thank you.

Judge Monk in Ex Parte Dansereau 19 L.C.J. 210. 1875

“… and if our Government is framed, in so far as circumstances will permit*, upon the model of the British Constitution, and inasmuch as it is so, the British Parliament, in conferring on us such a Legislature and such a Constitution, did impliedly and necessarily bestow on them, and vest in them, the power and the adequate authority of accomplishing and completely fulfilling the objects for which they were intended. Qui veut la fin, veut les moyens, may be a small maxim, but it is a true and pregnant one, and it is a principle of the common law, that where political or other such bodies are organized and powers granted, all the means and authority necessary for the exercise of their functions are also impliedly conferred, though not expressly mentioned.”

* Judge Monk means the fact that the British Constitution is unitary, but has been applied to a quasi-federal model in Canada.

A.H.F. Lefroy on “inherent powers of provincial legislatures”*

“Apart, however, from law-making, provincial legislatures have by virtue of being legislative bodies at all, such powers and privileges as are necessarily inherent in and incident to such bodies; and, having them, may regulate their exercise by statute or by standing rules, if they see fit to do so.”

* In his section “Inherent powers of legislatures apart from lawmaking”, pp. 91-93 in A Short Treatise of Canadian Constitutional Law With an Historical Introduction by W.P.M. Kennedy, The Carswell Company, Limited, 1918

Quotations from Joan Donnelly

writing in “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122

The concept of a court possessing “inherent jurisdiction” is unsettling to a lawyer educated in a constitutional tradition founded on the separation of powers and the supremacy of parliament.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 123.

Another cause for unease is the [inherent] jurisdiction’s apparently limitless character, inviting the prospect of judges, unconstrained by the gravitational pull of precedent, invoking the jurisdiction to justify all manner of eccentricity in decision-making.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 123.

A major source of the confusion that has arisen on the doctrine of inherent jurisdiction is that judges are conflating it with the concept of a court’s inherent powers. The two concepts are quite distinct. Inherent jurisdiction refers to a general and original jurisdiction of certain superior courts to hear and determine any matter at first instance. By contrast, inherent powers have arisen to consummate imperfectly constituted judicial power. Thus, whilst inherent jurisdiction is substantive, inherent powers are procedural.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 125.

Described as “spectacularly unhelpful”, this widely cited article [I.H. Jacob's "The Inherent Jurisdiction of the Courts"] has spawned widespread confusion in common law jurisdictions on the concept of inherent jurisdiction, causing judges, in demarcating the perimeters of the jurisdiction, to confuse it with a court’s inherent powers.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 126.

What Jacob is, in fact, referring to in the above passage are inherent powers. The error is not merely semantic: the blurring of the distinction between inherent jurisdiction and inherent powers is symptomatic of conceptual confusion. Whether one interprets Jacob’s passage as referring to inherent jurisdiction or inherent powers, it is an incorrect statement of the law.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 126.

Translated from the Latin, “jurisdiction” means “the power to speak the law”. Jurisdiction denotes the constitutionally mandated authority of a court to take seisin of and determine causes according to law and to carry sentencing into execution. Thus, it is axiomatic that jurisdiction is granted by law.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 126.

Jurisdiction cannot be unilaterally or arbitrarily assumed by a court or created by the consent of parties to a dispute requiring adjudication.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 127.

A power, on the other hand, is “an entitlement in law to use a procedural tool – to hear and decide a cause of action in the Court within jurisdiction”. An inherent power is exercisable by all courts. It is a power which is incidental and ancillary to the primary jurisdiction; the power is “parasitic” on the primary jurisdiction.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 127.

Inherent powers are part of the common law of courts or, alternatively, arise by implication from the separation of powers doctrine. A court invokes its inherent power in order to fulfil its constitutionally-ordained function as a court of law and to accomplish the administration of justice in a regular, orderly and effective manner.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 127-8.

Inherent jurisdiction originated as a common law doctrine.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 128.

The interaction between the express jurisdiction of the courts and their inherent jurisdiction will depend in each case according to the scope of the express jurisdiction, whether its source is common law, legislative or constitutional and the ambit of the inherent jurisdiction which is being invoked.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 130.

Inherent jurisdiction by its nature only arises in the absence of the express.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 130.

‘Where the jurisdiction of the courts is expressly and completely delineated by statute law it must, at least as a general rule, exclude the exercise by the courts of some other or more extensive jurisdiction of an implied or inherent nature. To hold otherwise would undermine the normative value of the law and create uncertainty concerning the scope of judicial function and finality of court orders insofar as they relate to inherent jurisdiction at common law.’

– Joan Donnelly in “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 130-31, citing Murray C.J. in G. McG v. D.V. (No.2), at 27.

[A]lthough inherent jurisdiction coexists with statutory jurisdiction, it is necessarily subordinate to it. A judge must exercise his inherent jurisdiction with the utmost restraint, ensuring that no judicially created construct operates to supersede a rule of statute.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 132.

Judicial review is a common law concept which traces its origin to Dr. Bonham’s Case of 1610. Sir Edward Coke, sitting as Chief Justice of England’s Court of Common Pleas, inaugurated the notion of judicial review when he declared “when an act of parliament is against common right and reason or repugnant, or impossible to be performed, the common law will control it, and adjudge such act to be void”.

– Joan Donnelly in “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 136 citing from Sir Edward Coke, The Selected Writings and Speeches of Sir Edward Coke, ed. Steve Sheppard (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2003). Vol. 1. Chapter: Dr. Bonham’s Case; see also the entry on “Judicial Review” in West’s Encyclopedia of American Law (Gale Group, Inc., 1998).

[T]he rule that a court is functus officio once its judgment is entered in the record is subject to the overarching constitutional principle that a court will not permit an unsound judgment to be used as an instrument of injustice thereby subverting curial due process and defeating the requirements of constitutional justice.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 141.

It is traditional for courts, in interpreting statutes, not to depart from established common law principles.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 146.

Inherent powers have arisen to supplement original jurisdictions. Essentially procedural in nature, inherent powers enable courts [to] give full effect to the primary jurisdiction thereby permitting them to fulfil their function as courts of judicature. All courts in the judicial hierarchy –- statutory and constitutional –- possess inherent powers.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 146.

[I]t is clear that inherent powers have been developed by courts and are, thus, a feature of the common law. Encapsulating their essence, Joseph refers to inherent powers as forming part of the “common law of courts”.

– Joan Donnelly in “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 147, citing Joseph, Constitutional and Administrative Law (note 12), at p. 807.

An alternative view is that inherent powers are implied by the doctrine of the separation of powers. Being entrusted with the judicial function of government, courts have a constitutionally-ordained duty to exercise their functions effectively and efficiently to achieve the due administration of justice.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 147, citing the Website of the National Center for State Courts. See “Inherent Powers”, available at www.ncsconline.org/wc/CourTopics/FAQs.asp?topic=InhPow.

Another argument postulating inherent powers as an element of the separation of powers doctrine is the idea that courts must have powers to protect the independence of the judicial function from encroachment by the executive and legislative branches of government. Thus, inherent powers are part of a court’s resources; they are a necessary adjunct to the judicial function, facilitating the courts in functioning within a gapless framework of regulation thereby preserving the principles of constitutional order.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 149, citing the Website of the National Center for State Courts. See “Inherent Powers”, available at www.ncsconline.org/wc/CourTopics/FAQs.asp?topic=InhPow.

Many inherent powers developed by the courts are now codified in court rules. However, it seems that not only do inherent powers coexist with rules of court, but where a rule is narrower in scope than the common law power, it does not extinguish the element of the power which remains unregulated by the court rule.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 148.

[I]nherent powers supplement and amplify court rules. [I. H.] Jacob defines inherent powers as performing three essential functions: (i) filling in gaps left by the court rules, thereby ensuring that judges are equipped with the necessary powers to properly discharge the adjudicative function; (ii) enabling judges [to] invoke powers against persons other than the parties to litigation; and (iii) granting to judges the power to punish offenders by fine or imprisonment.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 149.

A court has power to stay proceedings which are frivolous or vexatious. Although Irish judges use the words “frivolous” and “vexatious” interchangeably, Jacob enunciates a distinction between the terms, citing illustrative case-law. Thus, frivolous proceedings arise where a litigant trifles with the court, or where the entertainment of proceedings would constitute a waste of time, or when a claim is not backed by a rational argument. On the other hand, proceedings are considered vexatious where they are without foundation, or cannot possibly succeed, or have as their purpose some ulterior or improper purpose.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 157, citing I. H. Jacob, “The Inherent Jurisdiction of the Court”, 23 C.L.P. 23-52 (1970)

It would be incorrect to view inherent powers as an unplumbed reservoir which a court can tap into whenever it lacks jurisdiction to grant a relief which it considers desirable.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 160.

Judges, in developing the common law, must do so by extrapolating from the existing body of precedent. As Farley J. ventures: “Any decision based on [an inherent power] should be in the tradition of the common law – incremental extensions of existing law, judicially and judiciously arrived at on a reasoned basis using analogy from established principles where possible”.157

– Joan Donnelly in “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 160, citing Farley in “Minimize codification by expanding use of inherent jurisdiction”, The Lawyers Weekly, (2007) November, available at www.lawyersweekly.ca/index.php?section=article&articleid=576.

It is vital that judges distinguish between inherent jurisdiction and inherent powers, and be aware of the respective juridical foundations of the two concepts. The conflation of the two terms has impacted on the exercise of curial function warping judges’ perception of the true contours of their substantive and procedural powers.

– Joan Donnelly, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, 160.

I.H. Jacob on The Inherent Jurisdiction of the Court

*”On what basis did the superior courts exercise their powers to punish for contempt and to prevent abuse of process by summary proceedings instead of by the ordinary course of trial and verdict? The answer is, that the jurisdiction to exercise these powers was derived, not from any statute or rule of law, but from the very nature of the court as a superior court of law, and for this reason such jurisdiction has been called inherent.

This description has been criticized as being metaphysical, but I think nevertheless that it is apt to describe the quality of this jurisdiction. For the essential character of a superior court of law necessarily involves that it should be invested with a power to maintain its authority and to prevent its process being obstructed and abused. Such a power is intrinsic in a superior court; it is its very life-blood, its very essence, its immanent attribute. Without such a power, the court would have form but would lack substance. The jurisdiction which is inherent in a superior court of law is that which enables it to fulfill itself as a court of law. The juridical basis of this jurisdiction is therefore the authority of the judiciary to uphold, to protect and to fulfill the judicial function of administering justice according to law in a regular, orderly and effective manner.”

* , 23 C.L.P. 23-52 (1970)

Nota Bene: Urgent: there is a problem with the much-cited Lord Jacob in his famous article. Please read Joan Donnelly’s article, “Inherent Jurisdiction and Inherent Powers of Irish Courts”, Judicial Studies Institute Journal, 2009:2, 122, in which Donnelly rectifies Jacob and begins to distinguish inherent power from inherent jurisdiction, and set up categories for each.

The Doctrine of Abuse of Process,

by De VRIES Litigation,

27 February 2007The Supreme Court of Canada had this to say about abuse of process:

The doctrine of abuse of process engages the inherent power of the court to prevent the misuse of its procedure in a way that would be manifestly unfair to a party to the litigation before it or would in some other way bring the administration of justice into disrepute. It is a flexible doctrine unencumbered by the specific requirements of concepts such as issue estoppel.[1] -NOTA BENE ////////////// This footnote is not to the direct quote of the SCC. LOOK IT UP! //////////

As can be seen from the above passage, the focus of the abuse of process doctrine is on the integrity of the judicial process and not on the motive, however dishonourable, or status of the parties.

= = =

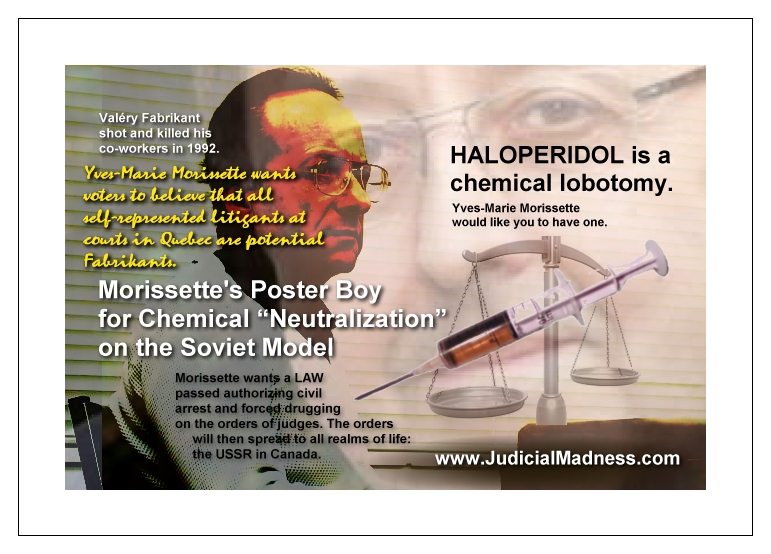

La Court of Appeal en R-U augmente de façon discutable la portée des « pouvoirs inhérentes » dans Ebert

Lord Woolf, à l’époque Master of the Rolls, en a méticuleusement retracé l’évolution dans Ebert v. Venvil. La question précise qui se posait dans cette affaire était de savoir si, dans l’exercice du pouvoir inhérent en question, la High Court pouvait assujettir à l’exigence d’une autorisation préalable de l’un de ses juges l’exercice d’un recours futur, d’un recours dans un autre district de la même Cour, ou d’un recours devant une autre juridiction (en l’espèce, le County Court). L’existence dans la législation britannique d’une disposition visant spécifiquement les recours vexatoires et créant une procédure distincte à cette fin donnait naissance à une complication : le Parlement avait-il souhaité que cette procédure prenne la place du pouvoir inhérent exercé dans Grepe v. Loam ? Malgré quelques décisions en sens contraire en Nouvelle-Zélande et en Australie, dont un arrêt de la High Court of Australia, la Cour d’appel dans Ebert v. Venvil conclut que le pouvoir inhérent a une portée étendue, qu’il a déjà été exercé de la sorte, et qu’il comprend sûrement la faculté d’assujettir à un contrôle les recours futurs comme les recours exercés devant le County Court (a fortiori du fait que cette juridiction est elle-même soumise au pouvoir de contrôle de la High Court).

– Yves-Marie Morissette, ecrivant dans Quelques réflexions sur la quérulence et l’exercice abusif du droit d’ester en justice, Barreau du Québec dans leur Congrès Annuel du Barreau du Québec (2002), ISSN 1185-7110, p. 21-22

The Court of Appeal in UK dubiously expands the scope of “inherent powers”

Lord Woolf, at the time Master of the Rolls, meticulously traced its evolution in Ebert v. Venvil. The precise question which arose in this case was to know whether, in the exercise of the inherent power in question, the High Court could subject to the prior authorization of one of its judges the exercise of a future recourse, a recourse in another district of the same Court, or a recourse before another jurisdiction (in the present case, the County Court). The existence in the British legislation of a provision specifically targeting vexatious recourses and creating a distinct procedure for this purpose gave rise to a complication: had the Parliament wished that this procedure take the place of the inherent power exerted in Grepe v. Loam? In spite of some decisions to the contrary in New Zealand and Australia, including a case at the High Court of Australia, the Court of Appeal in Ebert v. Venvil concludes that the inherent power has an extended range, that it had already been exercised, and that it surely included the faculty of subjecting future recourses to control such as the recourses exercised before the County Court ( a fortiori owing to the fact that this jurisdiction itself is subjected to the supervisory power of the High Court).

– Yves-Marie Morissette, writing in Some reflections on quarrelsomeness and the abusive exercise of the right to institute legal proceedings, originally published in French by the Barreau du Québec in their Congrès Annuel du Barreau du Québec (2002), ISSN 1185-7110, pp. 21-22

Chief Justice Mason, and justices Dawson, Toohey and Gaudron*

‘It is now accepted that superior courts have bvinherent power to grant declaratory relief. It is a discretionary power which “[i]t is neither possible nor desirable to fetter … by laying down rules as to the manner of its exercise.” However, it is confined by the considerations which mark out the boundaries of judicial power. Hence, declaratory relief must be directed to the determination of legal controversies and not to answering abstract or hypothetical questions. The person seeking relief must have “a real interest” and relief will not be granted if the question “is purely hypothetical”, if relief is “claimed in relation to circumstances that [have] not occurred and might never happen” or if “the Court’s declaration will produce no foreseeable consequences for the parties”.’

* Ainsworth v. Criminal Justice Commission [1992] HCA 10; (1992) 175 CLR 564 at pp. 581-2, cited in Re Chow Cho Poon (Private) Limited [2011] NSWSC 300 (15 April 2011)

Justice Anderson in Cocker v. Tempest, 151 ER 864 (1841)

“The power of each court over its own process is unlimited; it is a power incident of all courts, inferior as well as superior; were it not so, the court would be obliged to sit still and (to) see its own process abused for the purpose of injustice. The exercise of the power is certainly a matter of the most careful discretion.”

NOTES: that’s in Donnelly, see if that quote is right, was the judge correct?

= = =

Jerold Taitz writing in The Inherent Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court*

“The inherent jurisdiction of the Supreme Court may be described as the unwritten power without which the Court is unable to function with justice and good reason. As will be observed below, such powers are enjoyed by the Court by virtue of its very nature as a superior court modelled on the lines of an English superior court. All English superior courts, English colonial superior courts and the superior courts which succeeded them are deemed to posses such inherent jurisdiction save where it has been repealed or otherwise amended by legislation.”

* (Cape Town, South Africa: Juta Publishers, 1985)

Justice Morris of the House of Lords (England) in Connelly*

“There can be no doubt that a court which is endowed with a particular jurisdiction has powers which are necessary to enable it to act effectively within such jurisdiction. I would regard them as powers which are inherent in its jurisdiction. A court must enjoy such powers in order to enforce its rules of practice and to suppress any abuses of its process and to defeat any attempted thwarting of its process.”

* Connelly v. Director of Public Prosecutions, [1964] A.C. 1254

= = =

Justice Hallet in Golden Forest*

“The term inherent jurisdiction is not used in contradistinction to the jurisdiction of the court exercisable at common law or conferred on it by statute or rules of court, for the court may exercise its inherent jurisdiction even in respect of matters which are regulated by statute or rule of court. The jurisdiction of the court which is comprised within the term inherent is that which enables it to fulfill itself, properly and effectively, as a court of law. The overriding feature of the inherent jurisdiction [[[Looks like a mistake, conflation again, see Donnelly.]]] of the court is that it is a part of procedural law, both civil and criminal, and not a part of substantive law; it is exercisable by summary process, without a plenary trial; it may be invoked not only in relation to parties in pending proceedings, but in relation to any one, whether a party or not, and in relation to matters not raised in the litigation between the parties; it must be distinguished from the exercise of judicial discretion; and it may be exercised even in circumstances governed by rules of court ….

“In sum, it may be said that the inherent jurisdiction of the court is a virile and viable doctrine, and has been defined as being the reserve or fund of powers, a residual source of powers, which the court may draw upon as necessary whenever it is just or equitable to do so, in particular to ensure the observance of the due process of law, to prevent improper vexation or oppression, to do justice between the parties and to secure a fair trial between them.”

* Holdings Limited v. Bank of Nova Scotia (1991) 98 N.S.R. (2d) 429 (1990, NSCA)

Lord Diplock in Hunter v. Chief Constable of the West Midlands Police, [1982] A.C. 529, at p. 536

My Lords, this is a case about abuse of the process of the High Court. It concerns the inherent power which any court of justice must possess to prevent misuse of its procedure in a way which, although not inconsistent with the literal application of its procedural rules, would nonetheless be manifestly unfair to a party to litigation before it, or would otherwise bring the administration of justice into disrepute among right-thinking people. The circumstances in which abuse of process can arise are very varied; those which give rise to the instant appeal must surely be unique. It would, in my view, be most unwise if this House were to use this occasion to say anything that might be taken as limiting to fixed categories the kinds of circumstances in which the court has a duty (I disavow the word discretion) to exercise this salutary power.

NOTES: is that from Donnelly? Is Diplock right or wrong, double check Donnelly.

Further, the inherent power of superior courts to regulate their process does not preclude elected bodies from enacting legislation affecting that process. The court’s inherent powers exist to complement the statutory assignment of specific powers, not override or replace them. Courts must conform to the rule of law and, while they can exercise more power in the control of their process than is expressly provided by statute, they must generally abide by the dictates of the legislature. It follows that Parliament and the legislatures can legislate to limit and define the superior courts’ inherent powers, including their powers over contempt, provided that the legislation is not otherwise unconstitutional.

Notes: After reading Donnelly (and I don’t know where I got the quote above — it’s from DUBE – — from the head notes, “Per L’Heureux‑Dubé, McLachlin, Iacobucci and Major JJ. (dissenting)”;

), I wonder if that’s a mistake. Has somebody alleged that the legislature can legislate to limit or regulate “inherent power”, whereas perhaps it ought to have been said that it could legislatte to regulate inherent jurisdiction????

…..

Further, the inherent power of superior courts to regulate their process does not preclude elected bodies from enacting legislation affecting that process. The court’s inherent powers exist to complement the statutory assignment of specific powers, not override or replace them. Courts must conform to the rule of law and, while they can exercise more power in the control of their process than is expressly provided by statute, they must generally abide by the dictates of the legislature.

– from the head notes, “Per L’Heureux‑Dubé, McLachlin, Iacobucci and Major JJ. (dissenting)”;

- – -

para 78:

These inherent powers of superior courts are simply innate powers of internal regulation which courts acquire by virtue of their status as courts of law. The inherent power of superior courts to regulate their process does not preclude elected bodies from enacting legislation affecting that process. The court’s inherent powers exist to complement the statutory assignment of specific powers, not override or replace them: “The two heads of powers are generally cumulative, and not mutually exclusive” (I. H. Jacob, “The Inherent Jurisdiction of the Court” (1970), 23 Current Legal Problems 23, at p. 25).

NOTES: again, is this likely to be right or wrong in view of Donnelly?

- – -

88 The final guarantee that the process of the superior courts will not be undermined by a transfer of juvenile contempt of court ex facie to the youth courts, lies in the residual inherent jurisdiction of the superior courts to take such measures as may be required to preserve their process. [[[ Notes: given Donnelly, that statement may be a misuse of the term, it may in fact have to be corrected with the term "inherent power".]]] Should the administration of justice require that a particular case be tried in superior court, that court possesses the inherent power to hold such a trial. [[[again, is it in fact inherent power here, or inherent jurisdiction?]]] As discussed earlier, all rules of court must be read as subject to the inherent power of the superior court to do what is required to preserve their process. Where the use of a legislative provision or rule of court would itself amount to an abuse of the court’s process, the court may invoke its inherent jurisdiction [[[this person is flipping back and forth between the two terms, as if, am I right, they are one and the same, i.e., it's a "conflation" a phenomenon pointed to by Donnelly. And if the judge here is citing Jacob, then this indeed would be a likely conflation, subject to correction. ]]] to ensure that justice is done. Section 47(2) of the Young Offenders Act is no exception.

- – -

ALL the above, non-formatted quotes, are from:

This document: 1995 CanLII 57 (S.C.C.)

Citation: MacMillan Bloedel Ltd. v. Simpson, [1995] 4 S.C.R. 725, 1995 CanLII 57 (S.C.C.)

Parallel citations: (1995), 130 D.L.R. (4th) 385; (1995), [1996] 2 W.W.R. 1; (1995), 103 C.C.C. (3d) 225; (1995), 33 C.R.R. (2d) 123; (1995), 44 C.R. (4th) 277; (1995), 14 B.C.L.R. (3d) 122

Date: 1995-12-14

Docket: 24171

[Noteup] [Cited Decisions and Legislation]

MacMillan Bloedel Ltd. v. Simpson, [1995] 4 S.C.R. 725

= = =

INTERESTING QUOTE, DOUBLE-CHECK THE SOURCE & TEXT:

“Lord Diplock outlined the various ways in which justice might be prejudiced:

“The due administration of justice requires first that all citizens should have unhindered access to the constitutionally established courts of criminal or civil jurisdiction for the determination of disputes as to their legal rights and liabilities; secondly, that they should be able to rely upon obtaining in the courts the arbitrament of a tribunal which is free from bias against any party and whose decision will be based upon those facts only that have been proved in evidence adduced before it in accordance with the procedure adopted in courts of LAW; and thirdly that, once the dispute has been submitted to a court of law, they should be able to rely upon there being no usurpation by any other person of the function of that court to decide it according to law. Conduct which is calculated to prejudice any of these requirements or to undermine the public confidence that they will be observed is a contempt of court” (at p. 309).

(A-G v. Times Newspapers 1974)